January 27, 2005

Better

It's a pretty rough virus.

I'm starting to feel normal, but the feeling only lasts for an hour or so and down I go again like the bad battery in this very laptop (which should be replaced soon).

Last night, I got a hankerin' for a lullaby*, Glen Gould's Goldberg variations. Thanks to modern life, we can fetch up nearly anything we want online, so I dialed up my request in iTunes. I write "nearly" here because Mr. Jobs' gizmo doesn't stock Glen Gould's work. I had to download John Rusnak's version, which is serviceable. (He twiddles the keys more than I'd like sometimes... but what do I know? Musically, I'm a punk.)

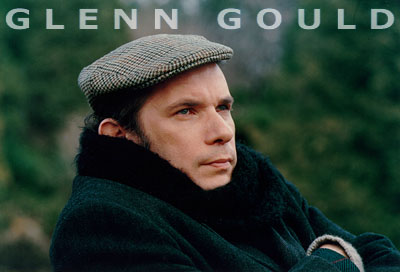

To communicate (no, indulge) my enthusiasm for Glen Gould's work, I googled to a fan site, where I found his picture. Also, read the 1955 Columbia Records press release, priceless:

Gould at the keyboard was another phenomenon ? sometimes singing along with his piano, sometimes hovering low over the keys, sometimes playing with eyes closed and head flung back. The control-room audience was entranced, and even the air conditioning engineer began to develop a fondness for Bach. Even at record playbacks Glenn was in perpetual motion, conducted rhapsodically, did a veritable ballet to the music. For sustenance he munched arrowroot biscuits, drank skimmed milk, frowned on the recording crew?s Hero sandwiches.

But check this site out, amazing!

"...Library and Archives Canada, which is the official repository for the archives of the late concert pianist, Glenn Gould."

This is where I found these snippets from Gould's statement concerning the Variations (first, a couple of paragraphs from the middle):

Nothing could better demonstrate the aloof carriage of the Aria, than the precipitous outburst of Variation 1 which abruptly curtails the preceeding tranquillity. Such aggression is scarcely the attitude we associate with prefatory variations, which customarily embark with unfledged dependence on the theme, simulating the pose of their precursor and functioning with a modest opinion of their present capacity but a thorough optimism for future prospects.

With Variation 2 we have the first instance of the confluence of these juxtaposed qualities -- that curious hybrid of clement composure and cogent command which typifies the virile ego of the Goldberg...

No flagrant jargon here, technical talk for the sake of precision as far as I can tell. Here, his finale:

It is in a short music which observes neither end nor beginning, music with neither real climax nor real resolution, yet music in which there exists a fundamental coordinating intelligence which we labelled "ego". It has, then, unity through intuitive perception, unity born of craft and scrutiny, mellowed by mastery achieved, and revealed to us here, as so rarely in art, in the vision of subconscious design exulting upon a pinnacle of potency.-- Glenn Gould

Amd there is this, from his advice to a graduating class (sooo much good stuff there to select from):

Somehow, I cannot help thinking of something that happened to me when I was thirteen or fourteen. I haven't forgotten that I prohibited myself anecdotes for tonight. But this one does seem to me to bear on what we've been discussing, and since I have always felt it to have been a determining moment in my own reaction to music, and since anyway I am growing old and nostalgic, you will have to hear me out. I happened to be practising at the piano one day -- I clearly recall, not that it matters, that it was a fugue by Mozart, K. 394, for those of you who play it too -- and suddenly a vacuum cleaner started up just beside the instrument. Well, the result was that in the louder passages, this luminously diatonic music in which Mozart deliberately imitates the technique of Sebastian Bach became surrounded with a halo of vibrato, rather the effect that you might get if you sang in the bathtub with both ears full of water and shook your head from side to side all at once. And in the softer passages I couldn't hear any sound that I was making at all. I could feel, of course -- I could sense the tactile relation with the keyboard, which is replete with its own kind of acoustical associations, and I could imagine what I was doing, but I couldn't actually hear it. But the strange thing was that all of it suddenly sounded better than it had without the vacuum cleaner, and those parts which I couldn't actually hear sounded best of all. Well, for years thereafter, and still today, if I am in a great hurry to acquire an imprint of some new score on my mind, I simulate the effect of the vacuum cleaner by placing some totally contrary noises as close to the instrument as I can. It doesn't matter what noise, really -- TV Westerns, Beatles records; anything loud will suffice -- because what I managed to learn through the accidental coming together of Mozart and the vacuum cleaner was that the inner ear of the imagination is very much more powerful a stimulant than is any amount of outward observation.

Oh yes, check out the recordings by Gould (the first one are in his words) at this link! Hours of outtakes, a treasure of a link.

Oh yes, the lullaby?"For this model..., we are indebted to Count Keyserlingk, formerly Russian envoy to the court of the Elector of Saxony, who frequently resided in Leipzig, and brought with him Goldberg, who has been mentioned above, to have him instructed by Bach in music. The Count was often sickly, and then had sleepless nights. At these times Goldberg, who lived in the house with him, had to pass the night in an adjoining room to play something to him when he could not sleep. The Count once said to Bach that he should like to have some clavier pieces for his Goldberg, which should be of such a soft and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights. Bach thought he could best fulfil this wish by variations, which, on account of the constant sameness of the fundamental harmony, he had hitherto considered as an ungrateful task. But as at this time all his works were models of art, these variations also became such under his hand. This is, indeed, the only model of the kind that he has left us. The Count thereafter called them nothing but his variations. He was never weary of hearing them; and for a long time, when the sleepless nights came, he used to say: "Dear Goldberg, do play me one of my variations." Bach was, perhaps, never so well rewarded for any work as for this: the Count made him a present of a golden goblet, filled with a hundred Louis d'ors. But their worth as a work of art would not have been paid if the present had been a thousand times as great."

(can't stop posting on this topic)

Posted by Dennis at January 27, 2005 12:35 AM

Check out this site for a skeleton's key to the variations.

Leave a comment