April 22, 2005

Be Mistrustful of History

ArtNet reproduced the text of a Kuspit speech, a revised version of a lecture given at the SITAC (International Symposium on Contemporary Art Theory) conference in Mexico City in January 2005.

He is delivering the usual scholarly treatment to the problem of the contemporary and historical in art. It's not so bad. A pretty deep subject to be sure, one that requires a Kuspit to handle it. I think about how museums have come closer to galleries in their function... about how difficult it is to get a handle on just what happened as modernity became postmodern... about the dilated character of art today...

Here's the first paragraph:

The Contemporary and the Historical

by Donald Kuspit

It has become excruciatingly difficult and even impossible to write a history of contemporary art -- a history that will do justice to all the art that is considered contemporary: that is the lesson of postmodernism. If writing history is something like putting the pieces of a puzzle together, as psychoanalyst Donald Spence suggests, then contemporary art is a puzzle whose pieces do not come together. There is no narrative fit between them, to use Spence's term, suggesting just how puzzling contemporary art is, however much its individual pieces can be understood.

Deeper into the essay, he pulls a memorable quotation:

"Be mistrustful of history," the Spanish poet Pere Quart wrote in his poem Ode to Barcelona, and he is right. "Dream it and rewrite it," he said, because it is only a dream -- a wish-fulfillment -- and thus never true to reality. History is an attempt to find consistency in -- to read consistency into -- the inconsistent contemporary. Replacing the healthy flexibility of the contemporary with the rigidity of history is an attempt to channel creativity in a certain direction and finally to control and even censor it.

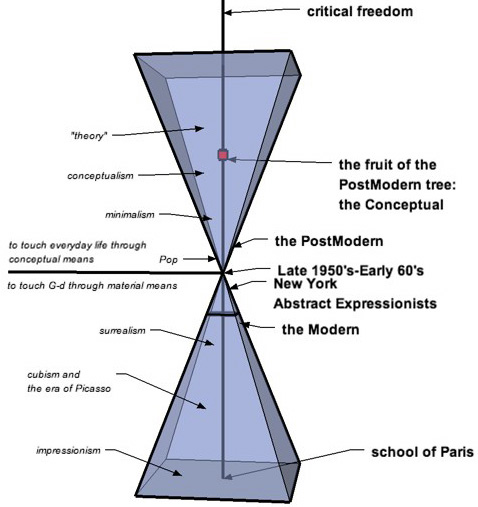

Well, feel free to mistrust my own fevered dream of art history that I am about to unfurl for you now. I happen to have in my files, a diagram of how the modern evolved into the postmodern. It has a lot of problems, but alas! I think of Didion's words (colophon) as I look for the sermon in the suicide:

In short, this is a description of how the modern became the postmodern in recent art history. Here are a few points to pin a few ideas together:

It is important to be able to define what it is to be modern. (It is amazing to me how many people in either the art or architecture worlds can't do this!) Here's my definition: To be modern is to reconcile the life you are lilving with the things you are making. This perspective is most certainly a reflection of my architecture undergraduate degree. The general view of the emergence of the modern in architecture is one of the disruption of the canon by rapidly developing modern technology. New building materials and techniques required an attempt to reconfigure a classical canon into a new (contemporary) one. Over time, efforts continued to fail as new innovations continued to disrupt any attempts to craft a stable narrative.

There are many other voices and narratives (one of the points of Danto's speech, as I uderstand it), but I tend to think of the modern project generally as a reach for transcendance, in blunt terms: to attempt to touch G-d through material means.

There was a crisis at the end of the fifties. Young artists like baby Warhol, baby Rauschenberg, Baby whoever-was-destined-to-contribute-to-Pop Art... they looked at the Rothkos, the DeKoonings and other greats and realized that they weren't going to touch G-d any better than the grizzled masters. So they took the Oedipal turn and flipped the paradigm:

Instead of touching G-d through material means, they endevored to touch everyday life through conceptual means.

I love the Lawrence Weiner quote: "We had to question the answers given to us in school." Artists at the end of the fifties and the beginning of the sixties questioned the answer of high modernism and flipped it on its head. A true revolution, Coprenican, like the invention of zero or negative integers. A cone of innovation reached an apotheosis and disappeared at its zenith. And what appeared was a raging mountain stream, a torrent of innovation that prized the conceptual over the material. Pop was followed by the Minimal, followed by the Conceptual, followed by Theory. The fruit of the postmodern tree was the conceptual, to be sure (Sol LeWitt, as far as I'm concerned). Art had to be dematerialized. It had to be in its essence, an idea. The stream flowed and broadened over time into a grand and stately river, soon into a slow and wide delta. That is where we are now: silted, fetid, and oozing out to sea, to be evaporated into oceanic clouds, ferried along the winds to mist the mountaintops.

Once again.

And what of painting? Implicated by its materiality, dammed as the ultimate patriarch of art, painting had to play the fool to get along after the inversion of the pyramid/cone, the revolution. Painting had to decry itself: bad painting, the Homer Simpson guise, the anti-aesthetic, the turn of the volume of paint to zero, the monochrome, reductions of all sorts, the subordination of paint to other art forms (photography, for instance). To be a painter in the thirty years before the 90's, one had to hide the paint in one way or the other, one had to paint in alienation. And even in the resurgence of painting in the 90's some artists had to communicate in an infantile language (verbally and pictorially), or otherwise take cues from the graphic arts to rate relevance.

There should be no surprise then that Pop has a sustained relevance in our time. But we should be taken aback that an era such as this has lasted without its own critical overhaul, now surpassing fifty years! Have we stopped questioning the answers given to us in school, even the answers that happened to have started off as questions long ago?

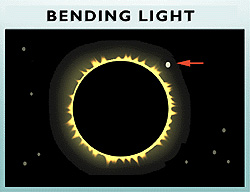

It was as if that to be able to see the stars nearest the sun, we had to cover it up. The stars are the other art forms: installation, photography, performance et al. Painting is the sun. And over time, we forgot that we are standing there, hands aloft. To be sure, every argument requires artiface but we eventually mistook the artiface for fact. We took it for granted. We forgot about the sun.

?Que pena!

Posted by Dennis at April 22, 2005 1:32 PM

1. Insightful analysis, it resonates.

2. Here in the delta there are no big landscape features to push against, isn't that what you're saying? No big answers to question. Many teeny tiny answers to question, if we bother, which, personally, I don't have the energy for. I'm guided much less by a sense of what others are doing and much more by intuition and instinct. Positioning oneself in the art world seems now to be less an act of nailing theses to cathedral doors, and more a game of Trivial Pursuit.

All conversations trail off in the mist you write of. We're less doctrinaire, which feels more open and democratic, but the price we pay is that we're never sure about anything but our own instincts.

We've reached the polar opposite of Vasari's dark age: too much of too great variety going on. The only real authority to speak of is the market. With hundreds of gallerists of widely varying tastes and patronages at the controls, there's little danger that any single movement will gel any time soon.

But then again, history is packed with surprises, so who knows what might happen next.

The only alternative to the hot and slow composting delta life is to rise into the mists and bubble out your own artworld. That's not so trivial.

Levitation is hard work!

that fits perfectly with what I see you doing -

using conventional paint and supports, but not using any conventional tools, apparently - ? is that right? no brush strokes etc.

painting as though no one had ever painted before - it often appears as though 'standard' rules of composition don't even matter to you (not always - some of those works on paper stand out to me as being more conventionally composed) - it really is your own art world.

In my experience, it feels as though I relearn painting each time I start a new painting. Or a new set, if I'm doing several at once. Do you ever experience that? Is that the writhing you wrote of before?

The Importance of a Truly Blind Artist, and The Impotence of Knowledge.

Yes, Bill, an intersting post.

Systems break! Systems have their good time--otherwise we

would all be living in the 19th century. I prefer reading history as an old combat--something like--the hard nosed against the hard nosed, until neither (the antagonist) pitters, more, neither (the protagonist) patters, upon the thinly thatched roof--of which neither are able to invigorate the true diversity of synthetic currency--but are bent on showing good proof.

I would like to mention that good artists are the masters of conceit and deception. This is how we unravel survival and show proof of a creative intelligence--not through lie but from not telling the truth. Nor, either, does a good artist follow deceit and misconception open-eyed.

thanks just the same, Dennis, and sorry about the crash - urghhh- I look forward to your response.

Brent, that's a great point you bring up. I see the conceit as a companion of exhibitionism. Is ideophany a word?

I see the deceit in a theatrical sense, almost a prestidigitation or a PT Barnum kind of thing. Is that what you're saying?

Bill,

I guess I was saying, as something is uncovered another thing gets hidden, not necessarily purposely so, none-the-less it happens because of the arrangement of certain situations. It's a fine line that wanders. Dennis's previous image post has a river that looks to head towards a dam. It doesn't physically get there, but it certainly looks like it is heading that way.