July 2, 2014

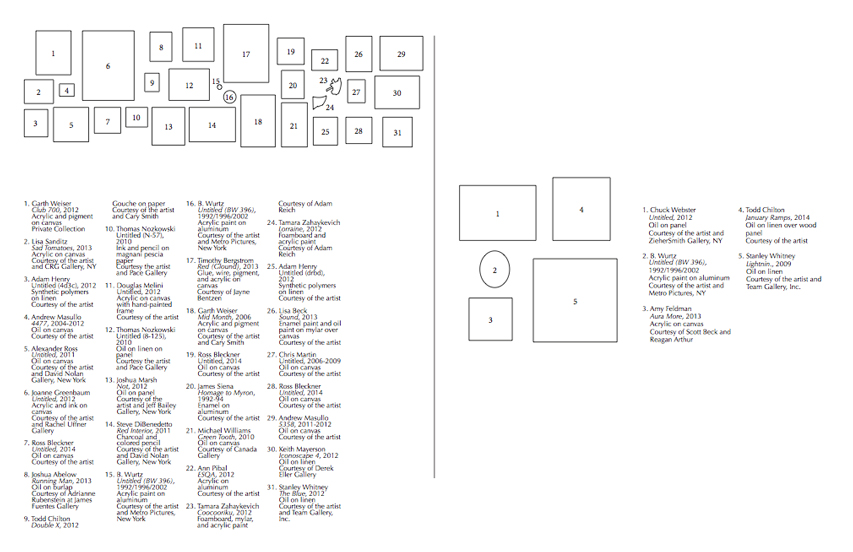

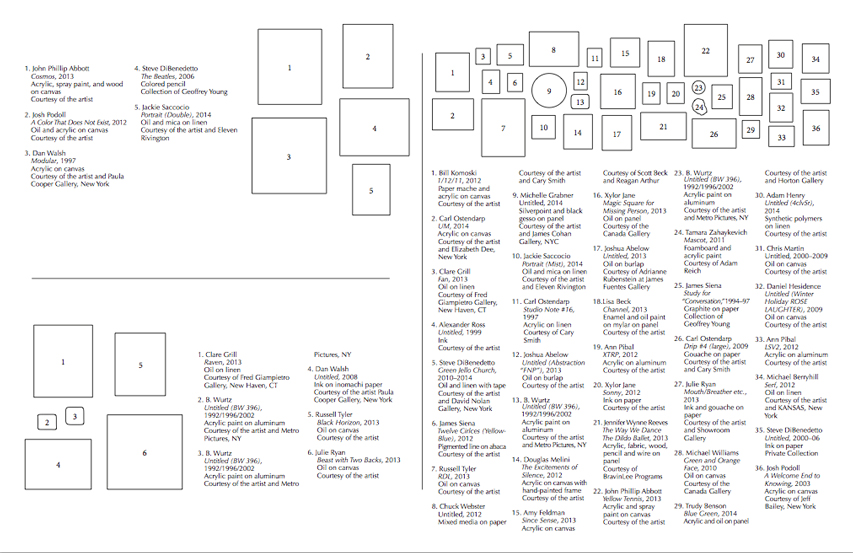

This One's Optimistic: Pincushion

Artist, painter and curator Cary Smith opened his show on Saturday, June 7, titled This One's Optimistic: Pincushion, a group show at the New Britain Museum in Connecticut, delivering remarks introducing the several artists in the exhibition who were present, a short exposition about painting in affirmation and ended with a heartfelt tribute to Jennifer Wynne Reeves, an artist beloved by many who was at that moment in hospice care. (She has since passed away as of this writing.) Fellow painter and favorite friend Joanne Greenbaum invited me to accompany her on the drive to Connecticut and see the show. The pleasure of the ride and conversation was doubled by the opportunity to see a show that is based on affirmation and a commitment to painting. I was full of curiosity about how, or even if my ideas about the embrace of painting would correlate with the other artists in the show.

Why is affirmation important today?

I've written elsewhere several times over in this blog about my motivations to commit to painting with affirmation. In capsule: my grad school accomplished its mission to deliver the reigning worldview of art and what passed as philosophical theory. The sharpest aspect was "the death of painting", the wellsprings of this came from various sources (Critical Theory was the dominant fashion of that moment, the end of the 80's), all of which can be grouped under the postmodern umbrella.

I believe that postmodernism ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. When the Cold War ended, so did the internal logic of the bipolar 20th century. I had expected to see articles in various art publications as they arrived each month that reassessed the end of an epoch, the anticipation of the dawn of a new one. But none arrived even as students quietly devoted themselves to painting in the 90's, in grad school studios all over the world, en masse. It was curious to me at the time that my attempts to bring up the subject of the end of postmodernism with my colleagues fell flat. The mere mention of the word itself at the time was avoided, frowned upon, considered naive. I concluded that to do so required questioning the authority of those who coined the phrase "Question Authority", that the reign of king Critical Theory was still considered too strong to counter. If you raise your hand to strike the king, as the saying goes, you must destroy him. Evidently, the king was still too strong, artists such as Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelly were in the midst of their rise and their recognition was in sight at the horizon. Therefore I concluded that my fellow young painters simply bypassed the stalemate. Crafty.

What was the hazard in dismissing the significance of the sunset of the postmodern empire? I believe that we are only beginning to register the cost of averting our eyes. You see it in Walter Robinson's coinage of the label Zombie Formalism. Robinson hangs a big part of the blame on Clement Greenberg's lingering influence, the "...straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting..." whose legacy was the emphasis on visuality over the material substance of painting. Greenberg ushered in the high modernism of abstract expressionism but he also presaged dematerialized, conceptual postmodernism. Jerry Saltz suggested in Why Does So Much NewAbstraction Look The Same? that young artists have lost faith in their ability to write subsequent chapters of art history. The New is simply no longer possible for them, originality is still too radioactive, and so they become "... industrious junior postmodernist worker bees, trying to crawl into the body of and imitate the good old days of abstraction, deploying visual signals of Suprematism, color-field painting, minimalism, post-minimalism, Italian Arte Povera, Japanese Mono-ha, process art, modified action painting, all gesturing toward guys like Polke, Richter, Warhol, Wool, Prince, Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, Wade Guyton, Rudolf Stingel, Sergej Jensen, and Michael Krebber." Robinson threw down the simulacrum card:"In our Postmodernist age, 'real' originality can be found only in the past, so we have today only its echo. Still, the idea of the unique remains a premiere virtue. Thus, Zombie Formalism gives us a series of artificial milestones, such as the first-ever painting made with the electroplating process (Kassay), and the first-ever painting done using paint applied in a fire extinguisher (Smith)." This indictment has been viral, seen in many other fronts of culture recently, even as we yet ignore the idiot light blinking so persistently on the dashboard. My favorite recent broadside is from Die Antwoord's Ninja's critical scream in Fatty Boom Boom:

Rappers r fucking boring ninja bashing dere brainz(Emphasis Mine.)

What happened 2 all da kool rapperz from back in da day?

Nowawayz all deze rapperz sound exactly da same

It's like 1 big inbred fuck-fest sis!...

This, is the hazard we risk.

Attempts to define both the modern and postmodern have always been difficult. It's hard to get a fix on ones bearings in the midst of the storm, but we are obliged to try. In the largest sense, to be modern is to reconcile the things one makes with the life one lives. The high modern was the era of the New York School of Abstract Expressionists, they tried to touch G-d through material means. The proto-postmodernists (Warhol, Johns, Rauchenburg, etc) couldn't touch G-d any better than Rothko and Pollock did. So they revolted in the most classic sense, they inverted the paradigm. Instead of touching G-d via materiality, they pointed at everyday life via conceptual means. They began in the most direct means with Pop, then dialed materiality down with Minimalism. Sol LeWitt was the fruit of the postmodern tree, turning the knob to zero. He established the sin aqua non of art-as-a-set-of-instructions. The storm of postmodernism was at its peak at this moment and it continued on with a spreading delta of ancillary movements: the personal-is-political, Critical Theory, and after a short interregnum in the early 90's with what I call CEO Art (artists --Hirst, Murakami, Pardo, Koons among others-- who model themselves as deal making chief executive officers, ref= Donald Trump's "Art of the Deal"). This last movement is yet another iteration of dematerialized art.

In the narrow sense of art movements, modernism and postmodernism were born as one from the ashes of the classical epoch. Modernism was first to blaze into prominence in an enchanted fit of idealism, finally babbling insipidly in tongues. Postmodernism succeeded with an empirical, skeptical refutation of modernism, it's' other, finally weaponizing irony in a gleam of nihilism. As in the opening lines of the Iliad, anger was its muse... and to complete the mirrored model, modernism was the delayed journey home. Negation motivates, saturates the postmodern. Painting had to die so that alt-media could live.

But that was then and this is now.

And so the question persists: how can an artist revolt against all of this? How can we revolt against revolution without resorting to the reactionary? I won't be so rash as to try to supply an answer to this ultimate question, but I know two things: 1) that a good place to start is to defy what is verboten (which for me and a legion of other artists is to approach painting in the affirmative) and 2) that any sensible response will be a synthesis, to preserve the gains won by both epochs modern and postmodern (for example, to embrace what was discovered by the anti-aesthetic and abjection in terms of painting). However the art of the early 21st century will be defined, it should profit from what was achieved in the 20th. The way forward might be to reject rejection, to heal the split, to combine the best of both modernism and postmodernism, to explore how they fit together.

Quality of invention, both in the overall image and well as the handling of materials. Every part meaningful. Originality, which conveys a sense of awareness of contemporary art, and art of the past, but most of all of the artist's own evolving path. Getting it "right" for whatever it is. Anything goes. Generosity of spirit, and positive character, like that which exists in those we most enjoy spending our time with. Freshness and a heightened sense of "believability". Realness doesn't have to look like something we know or understand. When we see it, we can feel it. Sometimes things we don't appreciate at first can stick with us, and take us forward. All art is essentially abstract at its core....

At first, I had mistaken the tribute to Jennifer Wynne Reeves to be indicated in the curation by the reference in the title of the "Pincushion", my associations ran to images of needles and IV's and the tribulations of hospice care. Cary corrected me, as he later wrote: "'Pincushion' was not about needles in the hospital, but like minded-ness... points of intensity all entering from different locations, but pointing in relatively the same direction. Just my perspective. And I wanted a conundrum in the title..." In addition to the image of all 40 artists entering the closed system of painting from different surface locations of painting's spherical pincushion, the idea of painting is also a compound one. If optimism is a force that is outward bound, centrifugal, then pessimism might be a force that is inward bound, centripetal.

This is a good instinct, to complicate the curatorial idea of affirmation, as I believe that the way forward has to be a synthesis (modern and postmodern) after all.

Posted by Dennis at July 2, 2014 6:59 AM

Its all pincushions and porcupines and my balloon ass is just trying to survive!

But seriously, I like your notion of the affirmative synthesis as a way forward. To me, postmodernism contributed 2 major things: one, bringing to the table players other than white, western males, and, two, expanding the list of factors that contribute to meaning-making to include form, content, context, media and material, process, and affect- maybe genre and style is in there as well.

Here is the thing for me. I teach art at a community college so I am hitting my students with everything from Felix Gonzales-Torres to Mark Ryden, from JMW Turner to Chris Burden, from Matisse to the Guerrilla Girls. In terms of reconciling these things, what a job they have!

As a teacher, I have found I have to reconcile these, in the affirmative, for myself and for my students. Its an easy task in the context of education, but a difficult one in the process of being a contributing artist where the need for negation and choosing teams is always present.

As a practitioner, I run into the reality that I work within a different institutional structure than a Kassay or a Katharina Grosse or a Koons, or a Willie Cole. All of whom run in different races than each other, function differently from each other, and exist within different institutional structures. Yet it is all Art, ostensibly running in the same race called “art history”. Cray-cray!

As far as painting is concern, I have a complicated relationship to it in the realm of an embattled son/father situation. I love painting. I love seeing it and reading about it and doing it. But, I also hate painting. I hate that there is so little room to navigate. I hate that the sirens (going back to your Iliad reference) of the marketplace constantly call out to me while I have myself bound to the conceptualist/ installationist mast. I know I would love to see this show and all the different effects, it would be like a kid at a candy store. I know I would enjoy the conceptual game of wiggling my work into theirs, seeing how it compares/contrasts.

But, how do you “revolt against revolution without being reactionary?” good question!