June 8, 2017

Art Treats Death

While listening to The Partially Examined Life podcast, Episode 164: Dostoyevsky's "The Idiot", , the (part one and part two), I thought about this Spring's intramural controversies involving what I call lane crossing in the realms of politically charged art. In both cases -Dana Schutz's painting of Emmitt Till shown in the 2017 Whitney Biennial and Sam Durant's "Scaffold" (2012) recently installed and deinstalled at the Walker Art Center's Minneapolis Sculpture Garden- the long accepted practice of appropriation art led both artists (and the art world at large as well) into blithely sampling conceptual subjects deep in the territories of marginalized ethnic groups. The division into identity group territory has long been part and parcel of the politics of our art world (Left, if the reader doesn't already know) and the assumption that movement between territories could be facile has been caught short by passions inflamed in minority communities who feel that they were shallowly treated as mere instruments for the purpose of achieving power in the world at large.

The way out of the trouble, and the way into the communities that are used as subjects of art making lies in more than proclaimed depths of feeling -the shaky ground of subjective claims- but in an actual and sustained involvement in their world. This recourse is for the artist to get in there deep and discover something about the subject and herself along the way, to live out empathy in the raw.

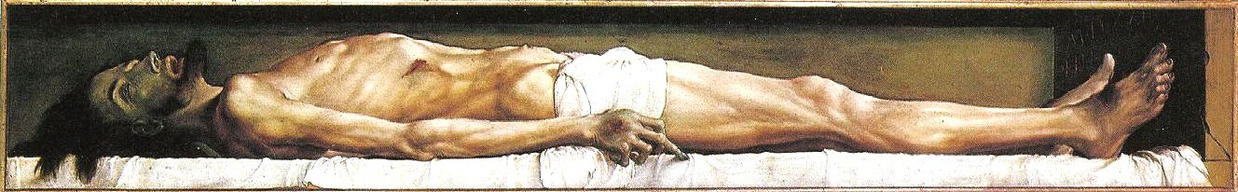

In the PEL discussion of The Idiot, the discussion turned to a moment in Switzerland when Dostoyevsky first encountered "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb" (1520-22) by Hans Holbein the Younger. He was transfixed in awe for a prolonged period of time. Since he was prone to fits of epilepsy, physically fragile, his wife was worried for his health and pulled him away from the gallery. Dostoyevsky wrote about this moment, porting his experience into the character of Ippolit. (This segment mentioned in the podcast is appended below.) What is demonstrated here is the power of art in painting and writing to convey the extremities of existence from the 16th and 19th centuries. The question for our secular art world is whether the diminution of the Judeo-Christian tradition has deprived us of the sweep of epic scope and with it, the depths of true empathy -the ability to share the feelings of another. The ironic, intellectually cautious, distancing legacy of Appropriation art that developed in the postmodern chapter of the 80's might have shortchanged the arts of our time and left us unprepared to authentically bridge the differences between peoples.

Holbein and Dostoyevsky made it look so easy.

"When I arose to lock the door after him, I suddenly called to mind a picture I had noticed at Rogozhin's in one of his gloomiest rooms, over the door. He had pointed itout to me himself as we walked past it, and I believe I must have stood a good five minutes in front of it. There was nothing artistic about it, but the picture made me feel strangely uncomfortable. It represented Christ just taken down from the cross. It seems to me that painters as a rule represent the Saviour, both on the cross and takendown from it, with great beauty still upon His face. This marvellous beauty they strive to preserve even in His moments of deepest agony and passion. But there was no such beauty in Rogozhin's picture. This was the presentment of a poor mangled body which had evidently suffered unbearable anguish even before its crucifixion, full of wounds and bruises, marks of the violence of soldiers and people, and of the bitterness of the moment when He had fallen with the cross--all this combined with the anguish of the actual crucifixion."The face was depicted as though still suffering; as though the body, only just dead, was still almost quivering with agony. The picture was one of pure nature, for the face was not beautified by the artist, but was left as it would naturally be, whosoever the sufferer, after such anguish. I know that the earliest Christian faith taught that the Saviour suffered actually and not figuratively, and that nature was allowed her own way even while His body was on the cross.

"It is strange to look on this dreadful picture of the mangled corpse of the Saviour, and to put this question to oneself: 'Supposing that the disciples, the future apostles, the women who had followed Him and stood by the cross, all of whom believed in and worshipped Him--supposing that they saw this tortured body, this face so mangled and bleeding and bruised (and they must have so seen it)--how could they have gazed upon the dreadful sight and yet have believed that He would rise again?'

"The thought steps in, whether one likes it or no, that death is so terrible and so powerful, that even He who conquered it in His miracles during life was unable to triumph over it at the last. He who called to Lazarus, 'Lazarus, come forth!' and the dead man lived--He was now Himself a prey to nature and death. Nature appears to one, looking at this picture, as some huge, implacable, dumb monster; or still better--a stranger simile--some enormous mechanical engine of modern days which has seized and crushed and swallowed up a great and invaluable Being, a Being worth natureand all her laws, worth the whole earth, which was perhaps created merely for the sake of the advent of that Being.

"This blind, dumb, implacable, eternal, unreasoning force is well shown in the picture, and the absolute subordination of all men and things to it is so well expressed that the idea unconsciously arises in the mind of anyone who looks at it. All those faithful people who were gazing at the cross and its mutilated occupant must have suffered gazing at the cross and its mutilated occupant must have suffered agony of mind that evening; for they must have felt that all their hopes and almost all their faith had been shattered at a blow. They must have separated in terror and dread that night, though each perhaps carried away with him one great thought which was never eradicated from his mind for ever afterwards. If this great Teacher of theirs could have seen Himself after the Crucifixion, how could He have consented to mount the Cross and to die as He did? This thought also comes into the mind of the man who gazes at this picture. I thought of all this by snatches probably between my attacks of delirium--for an hour and a half or so before Kolia's departure.

"Can there be an appearance of that which has no form? And yet it seemed to me, at certain moments, that I beheld in some strange and impossible form, that dark, dumb,irresistibly powerful, eternal force.

"I thought someone led me by the hand and showed me, by the light of a candle, a huge, loathsome insect, which he assured me was that very force, that very almighty, dumb, irresistible Power, and laughed at the indignation with which I received this information."

F.DOSTOEVSKY,

The Idiot, Part III, Chapter 4

(Emphasis Mine.)

Posted by Dennis at June 8, 2017 10:06 PM

Leave a comment