December 27, 2013

December 26, 2013

Lita Barrie: Painting with a Punch

I'm happy to announce the republication of Lita Barrie's "Painting with a Punch" as published this week in ArtWeek.LA. As Lita noted in an end note to the piece: "This essay is an updated, expanded version of an earlier essay "Painting with a Punch" that first appeared in the artist's catalog, Dennis Hollingsworth, published by Andre Buchmann Galerie, Koln, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo and Chac Mool Gallery, Los Angeles. Power Zoom Printing, Los Angeles. 2000."

The article has been aggregated by Painter's Table:

Lita and I have been good strong friends for years. Conversation between us is easy and flows without regard for the clock, the best sign of friendship. It was natural for me to ask her to write a piece for the catalog -and fortunate for me that she agreed- back in 2000. Here is her bio via ArtWeek:

I urge you to visit Dennis Hollingsworth: Painting with a Punch to read the essay properly with the accompanying images that illustrate it. I've posted the essay in its entirety sans illustrations below the fold, believing that there is endurance and persistence in ubiquitous repetition:

ARTWEEK.LA, Vol. 147 December 23, 2013 - Print the December 23, 2013 IssueDecember 23, 2013, Cover Stories, Cover Story, Features

Tuesday, Dec 24, 2013

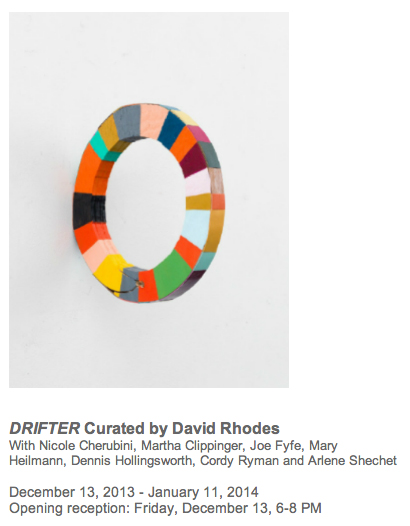

In this first of a two-part essay, Lita Barrie analyzes the thoughtful physicality in Dennis Hollingsworth's corporeal paintings. Hollingsworth's new paintings are on view in Drifter, a group exhibition at Hionas Gallery December 13, 2013 - January 11, 2014 and were included in the Miami Art Fair - Michael Kohn Gallery Booth C18, December 4-8, 2013.

Dennis Hollingsworth: Painting with a Punch Why do I think of Palahnuick's Fight Club when I look at Dennis Hollingsworth's paintings? It is because a brush stroke, like a punch, can have no intellectual mediation if it is going to have impact. Thought impedes these actions because their power derives from the body. Nevertheless, a brush stroke, like a punch, is also a culturally loaded sign. It can be read as a signifier of authority, dominance, assertion - and all that politically incorrect macho stuff.

Today punching is confined to sanctified spaces like gyms - where its wild power is tamed in corporate, clean, co-ed environments. The current vogue for male bashing has made men too afraid of being ridiculed as testosterone crazed animals to revel in punching outside the parameters of gyms. Tough babes might be sexy but tough guys are passé. A similar marginalization applies to the white male abstract painter - taunted by accusations from politically correct conceptualists, of being reactionary and perpetuating a worn out modernist legacy.

Nevertheless, as the success of Palahnuick's dark satire, Fight Club and other dark classics like Krakauer"s Into The Wild suggest, a consumer culture of licensed brand name identities cannot satisfy the human longing for experience in the raw. In a technologically simulated world of numbed-out disassociated experience, there is little opportunity to feel alive in the moment. However, as Fight Club suggests, when the primal human shadow is unleashed in unpremeditated physical action, fear disappears and a real sense of being alive in the moment occurs. As Tyler says," You aren't alive anywhere like you're alive in Fight Club."

The power of instinctual primitive action can be felt - but not discussed. "Fight Club isn't about words" as Tyler says. Nor is the process of painting. Of course, this view is not in keeping with the dominant semiotic theory in the art world which - for the last four decades - has emphasized the role of linguistic mediation over direct physical experience. An intriguing parallel might be drawn between Fight Club's spoof on the proliferation of twelve step support groups in society at large and the spread of the semiotic virus in academic art talk circles. Both use talk therapy and group identification, to mask the fear of acting spontaneously and taking risks. The academic semiotic virus has paralyzed spontaneous action in art schools, by creating a disembodied intellectualism which prefers the ugly (in "pathetic art" or "abject art") because it is considered more serious, while distrusting the senses - hence beauty is banished as decorative. Nevertheless, the Greek word aesthesis means "knowledge of the senses." In Immanuel Kant's aesthetic philosophy (currently regaining importance through Neo-Kantian philosophers) the feeling of pleasure in contemplating beauty, the sublime and the melancholic is based on reflection -hence these are intellectually based "aesthetic emotions." (1)

Just as the modernist emphasis upon dumb intentionality reached its reductio ad absurdum when artists claimed that anything they did physically was art (even Jackson Pollock's public pissing in Peggy Guggenheim's fireplace), the postmodern emphasis upon linguistic mediation has reached an equally reductive absurdity when art school theorists dismiss drawing as a wrist skill and turn art into a form of sound bite discourse.The outdated Cartesian mind/body separation has simply been reversed and theory has become the new thought police, reducing art to pseudo philosophy. It is a sad irony that art - a form of communication that precedes language - has been buried under argot, in a time when we are moving increasingly into a visual based culture - which is technologically simulated and desensitizing.Meanwhile, new science emphasizes relativity and the interconnections between mind/body, subject/object and inner/outer realities - which have been re-conceived as complementarities instead of polarities. The dynamics of communication have shifted to an emphasis upon making links between the seen and the unseen. In the context of this scientific paradigm shift, the postmodern emphasis upon the critique of cultural determinants has become as reductive and one-sided as the modernist emphasis upon the thoughtless emotive expression of isolated subjectivity. Both over-valorize outmoded dichotomies. So where does that leave painting?

Dennis Hollingsworth's paintings raise playful questions about the paradoxical position of abstract painting today - caught in the impasse between opposing camps. While Hollingsworth is highly skeptical about the conventions that inscribe painting, he also recognizes the impossibility of working without them. He uses this paradox as the impetus for his work - turning the painterly process into a critical reflection upon itself, that constantly raises new questions about its own modus operandi.

For Hollingsworth, the lessons of this relativistic era lie in the ability to flow and create fluid hierarchies - so that the critique becomes more intimate with the subject. Hollingsworth cites Joan Didion's notion of "the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience" which she says is frozen with "the impression of a narrative line upon disparate images." (2) This "shifting" flow of impressions interests Hollingsworth more than a fixed reading that would arrest the phantasmagoria. Hollingsworth prefers what he calls a "fugitive schemata" which allows each move to map out several more moves at once - creating an impression of paint moving over paint in a way that is endlessly interpretable. Hollingsworth's layered surfaces become a self-reflective space in which questions do not admit the closure of an answer - endings become beginnings, outer turns into inner and viewers are left to make of it what they can.

Hollingsworth emphasizes the importance of keeping himself "off balance" so that the painting process becomes a series of "what happens if...." strategies. The curiosity and sense of exuberant joy that underlie Hollingsworth's paintings, have an infectious quality which holds the viewer's attention. We see his cherishment of paint in marks that recreate themselves over and over again - becoming one with their medium. Paint is the lifeblood of these paintings and it is by pulling strength from movements of paint that Hollingsworth tests their limits - only to return to his initial starting point with a new determination to upset "the givens" by reformulating the problem in a different strategy of checks and balances. The wetness of the paint is related to drying time, but Hollingsworth's paint handling keeps the paint wetter. Hollingsworth's own pleasure in the painting process happens when the paintings are wet - and he re-creates this moment of wetness in a wet field to allow the viewer the same intimate pleasurable experience.

While many artists prefer to follow the dictates of vogue critical dogmas, Hollingsworth belongs to that smaller group of courageously individualistic artists who are receptive to the larger climate of ideas - that find a way into the artistic process, more subliminally. Hollingsworth's fascination with the energy that can be drawn and released from paint and the vibrant beauty of paint's physicality, reflects the quantum era - which is based on the inter-relationship between energy and matter. Hollingsworth creates an artistic synthesis of thought/action in the medium of paint, instead of collapsing into outdated modernist/postmodernist polarities by bridging the divide between mind/body - which subtly reflects the times.

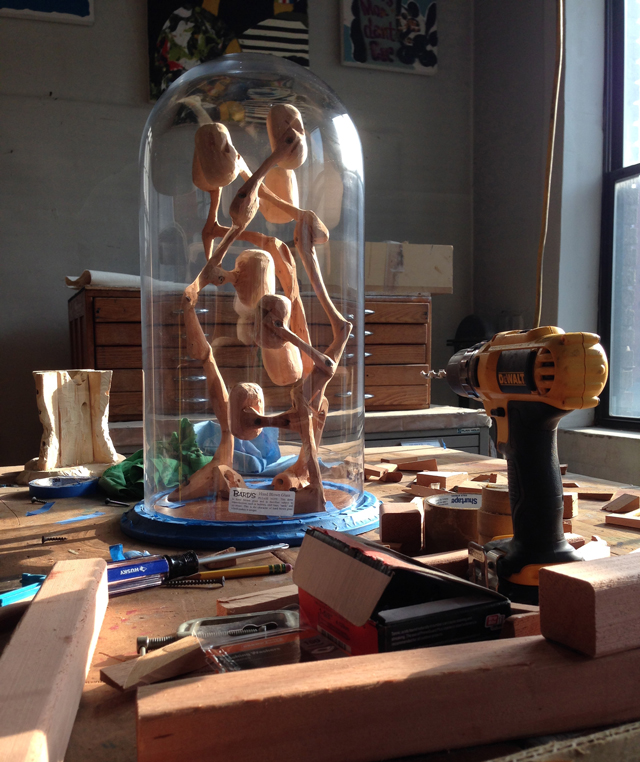

It is revealing that Hollingsworth's entrée into painting is via architecture - giving him a broader concept of what it means to be an artist and a sense of freedom to use building implements like dry wall tools and palette knives to pull paint in non-traditional ways. This love of architecture is behind Hollingsworth's use of bigger tools - to build large areas of color in bulldozing actions which lead to a next action of either enhancing or covering. These building tools allow brevity which creates an arrested quality, so that every action is frozen in its best form. The concept of a "series of edits" is an architectural idea: based on surveying land, pouring foundations and constantly correcting mistakes in the structure of the wood and the dry wall. Hollingsworth enjoys this process of "correcting mistakes" because he says " every application of paint has a beautiful aspect." He continually tries to isolate these beautiful aspects in the painting process and "cover up not so beautiful aspects." Hollingsworth begins paintings by spending time with a blank canvas until he can start in a way that will not "foreclose beforehand what happens." He says he likes to "enter a certain territory without wanting to prematurely craft an end game" while simultaneously accepting the apparent contradiction that he "eliminates the surprises along the way." Hollingsworth's paintings are never the same, but always one of a kind - as Robert Rauschenberg advised him.

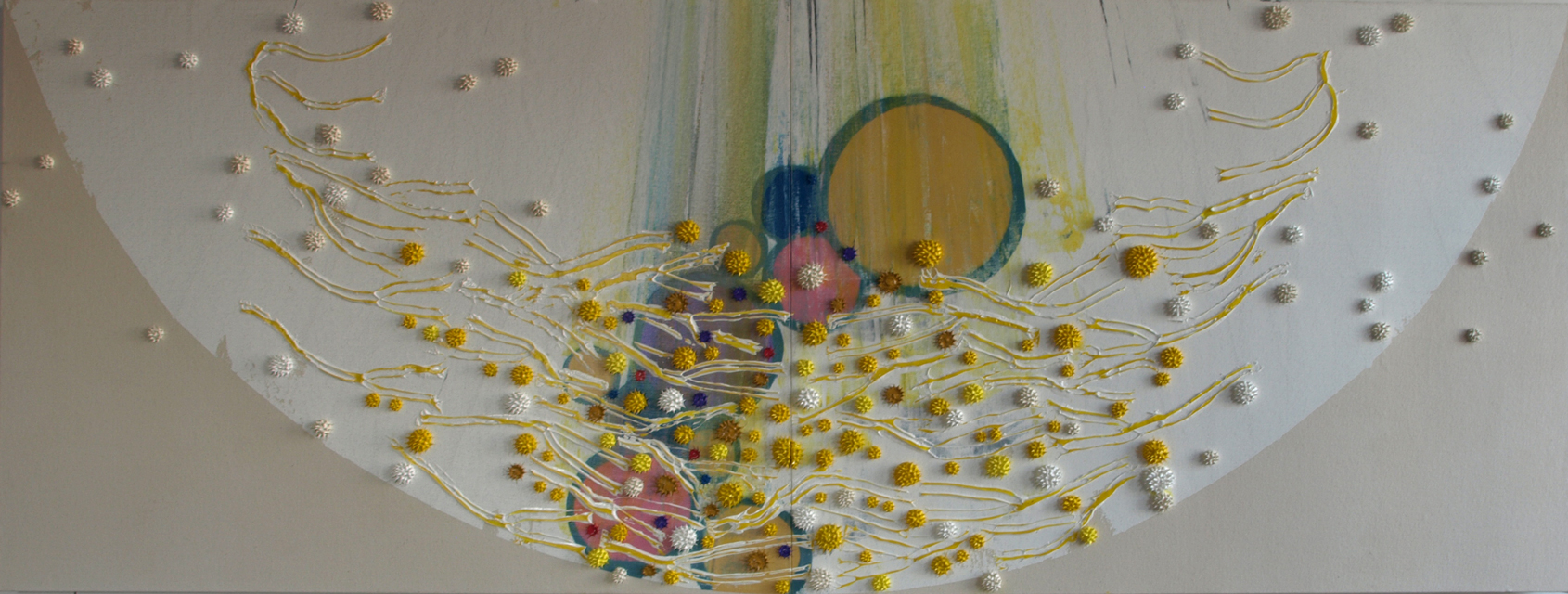

Over the last fifteen years, Hollingsworth has used custom made origami-like tools cut from stiff cardboard to spike pools of wet paint so that they crystallize and compound into spiny paint elements - that give the impression of monads communicating with one another, by vibrating. These natural spinning shapes are often found in nature - but still keep the character of the paint itself, which dries from the surface into the interior. Hollingsworth's appeal to nature is influenced by his love of Antoni Gaudi from years living in Barcelona - where he has another studio. The corpuscular monads also have an underwater sea life quality, which Hollingsworth explores in beautiful terrines composed of sculptural daubs of thick paint. After Hollingsworth relocated from Los Angeles to New York last year, he began to further develop the sculptural possibilities of using armature with the plastic possibilities of impasto paint. The bright colored monads in these terrines, recall Jacques Cousteau's underwater world, which has a strong influence on Hollingsworth's lifelong passion for underwater nature - including spending time as a sailor in his youth.Hollingsworth's non-traditional approach to painting is also influenced by his background in fencing which taught him that by drilling choreographed physical actions into muscular memory, the mind is freed to recognize ways of disrupting an opponent's pattern. By employing this fencing strategy in painting, Hollingsworth has developed the "chops" to recognize patterns fast enough to disrupt them. Unlike the old modernist school of slam dunk action painters who shun thought processes and the postmodernist school of image scavenging conceptualists who shun real physicality, Hollingsworth combines thought and action with a measured precision which makes his paintings very contemporary - yet they also have a classical ancestry that reaches back from Gaudi to Goya's love of the phantasmagoric.

The phenomenologist philosopher, Merleau - Ponty insists that "it is by lending his body to the world that the artist changes the world into painting." (3) The shifting digressions of Hollingsworth's movements of paint - returning over and over again to their generating axis, vividly illustrate Merleau-Ponty's idea that the world is re-created in painting through the mediacy of the painter's own body, "in a system of exchanges between seeing and the seen."

Hollingsworth's paintings are the inverse of what Hal Foster calls "the expressive fallacy" (4): that artists create to express themselves. As Foster argues, "mediated expressions preceded the artist: they speak him rather more than he expresses them." (5) Instead of falling into this outmoded fallacy, Hollingsworth reveals himself through his intellectual approach to the physicality of the painterly process. When modernist painting escapes into bodiless painterly gestures it becomes inflated with narcissistic claims of "personality". When postmodern art escapes into appropriating banal images from the mass media spectacle, it offers nothing worth discovering and nothing worth feeling.However, the body has always generated the most powerful metaphors for painting, because as Merleau-Ponty argues, every painterly technique "is a technique of the body." (6) Barbara Maria Stafford suggests that the survival of art may depend on reclaiming its relation to the body as a "locus" for experiencing the world from a phenomenological perspective - of the inside out - rather than as just a semiotic sign or image. She argues that we need art today that is "anchored in something that isn't simulated, degraded and cerebral" (7) - which is a tendency that results from the over-valorization of the mind over the body.

Hollingsworth's corporeal paintings are "anchored" in an intensely masculine, visceral awareness that insists on the embodied presence of a painterly mark. Stafford argues that we need art that reminds us that we are "incarnated on earth, and we have spirit and flesh and that the two have become one." (8) Hollingsworth's luscious, polyrhythmic paintings are constantly searching for this fluid integration of mind and matter through an intellectual awareness of the way thoughtful physical action can be embodied in the medium of paint - which he loves for its fleshy quality.

Hollingsworth's paintings demonstrate that enthusiasm embodies the intellect - and creates a flowing, fluid experience, that binds mind and body together. Perhaps, in the final analysis, the reason that Hollingsworth's corporeal paintings remind me of Fight Club is that he also recognizes that the antidote to the schizophrenia of living in a numbed-out, disassociated, media consumer spectacle lies in unifying thought and action to heal a split sense of self - an integration his paintings embody in an exuberant, joyful way.

References

1 Brady, Emily and Haapala, Arto "Melancholy as an Aesthetic Emotion" Contemporary Aesthetics Vol. 1. 2003

2 Didion, Joan The White Album: Essays. Simon and Schuster.1979.

3 Merleau -Ponty, Maurice "Eye and Mind" Art and Its Significance. An Anthology of Aesthetic Theory Ed Stephen David Ross. State University of New York Press. 1994.

4 Foster, Hal "The Expressive Fallacy" Recodings. Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics Ed Hal Foster. Bay Press.1985.

5 Foster, Hal Op.cit.

6 Merleau -Ponty, Maurice Op.cit.

7 Stafford, Barbara Maria "Interview" by Suzanne Ramyak, Sculpture. May/June1994.

8 Stafford, Barbara Maria Op.citNote

By Lita Barrie

Special thanks to Dennis Hollingsworth for many in-depth conversations, gallery and studio visits in an eighteen year traveling dialogue - from Los Angeles to New York - which helped develop insights into his painting process.

This essay is an updated, expanded version of an earlier essay "Painting with a Punch" that first appeared in the artist's catalog, Dennis Hollingsworth, published by Andre Buchmann Galerie, Koln, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo and Chac Mool Gallery, Los Angeles. Power Zoom Printing, Los Angeles. 2000.

December 24, 2013

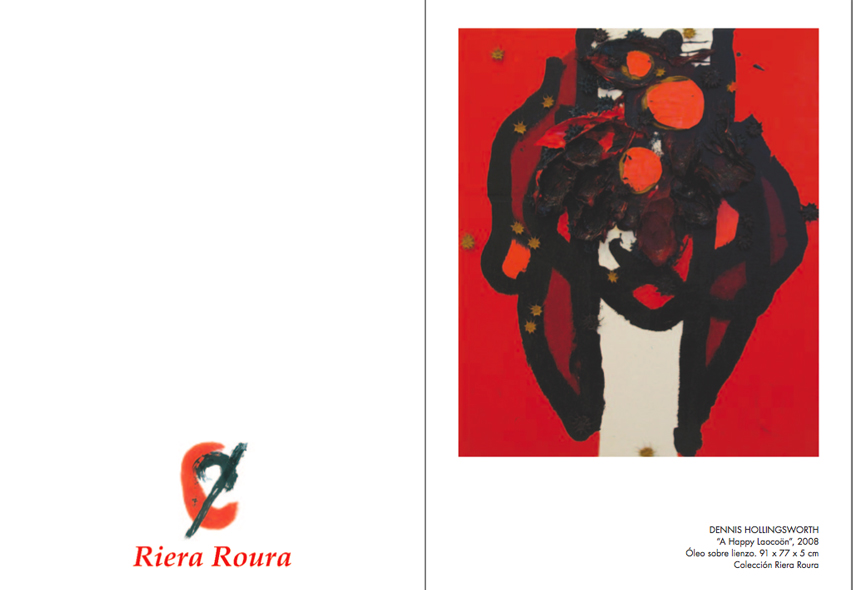

merry xmas from Riera Roura

Riera Roura is a business based in Barcelona Spain, owned by a collector who is the owner/custodian of my paintings.

December 23, 2013

December 12, 2013

Opening Tomorrow

Here is the press release:Drifting between painting and sculpture, art and architecture, plasticity and materiality, this impressive artist roster works with everything from acrylic and oil to ceramics, leather, fur, metals and wood, and they do so without exclusive preference for any particular medium. In both appearance and execution, each piece goes beyond a prescribed category; a hybridization occurs that doesn't actively defy categorization so much as embrace what can

be achieved when painting and sculpture complement each other in unexpected ways within the same form. Historical precedents can be found in Picasso's Glass of Absinthe (1914) and Oppenheim's My Nurse (1936), as well as the works of Moira Dryer from the 1980s.

"The migration of shape, form, color and material from one long established category to another, whether stopping just short of or completing the journey is a feature of new painting and sculpture. Territory is informally taken or exchanged in all the artists' work that comprises this exhibition. Vernacular materials often combine with fugitive color, the works here are happy in their homelessness and independent in a newfound openness that avails itself of historical tropes as much as the haptic fun of the present tense. Fictive illusionism and the real of the everyday have no need to be strangers in these works." - Curator David Rhodes

The opening reception for Drifter will take place on Friday evening, December 13 from 6-8 PM.

Hionas Gallery was founded in the spring of 2011, opening its initial exhibition space at 89 Franklin Street in TriBeCa. In January 2013 the gallery moved to 124 Forsyth Street in the Lower East Side. The gallery's mission is to invite contemporary and emerging artists, working in all variety of media, to participate in monthly solo exhibitions to showcase their latest work and artistic vision. Past invited exhibitors have included Marina Adams, Siri Berg, Karlos Cárcamo, Ariane Lopez-Huici, Charles Lutz, David Rhodes, Rebecca Smith and Jessica Stoller, to name a few. For more info visit www.hionasgallery.com

###

December 10, 2013

La Musica Notturna

La Musica Notturna delle Strade di Madrid. No. 6, Op. 30" by Boccherini

I love finding music and its covers by various people on YouTube. This is a wonderful expression and expansion of humanity, of pop culture and its dissemination, a faint echo of how music used to spread through sheet music and every parlor had a piano or guitar on hand for evening's entertainment. The internet lets us reverse the one way street of popular culture, where the labors of love by the amateur brings back in this time, the original meaning of the word. The subtle variations between each performer highlights their humanity. I can't help but use this as a lens to view the current condition of contemporary art and wonder what accidental structures -such as the enthusiastic democratic spontaneous embrace of the internet by sincere amateurs, linked to high and popular art- have in any way similarly affected today's art world?

Museums were created at a time when the art world was much, much smaller than it is today, I am thinking of populations of a few thousands versus the several (hundreds of?) millions of this day. This is similar to how television had evolved: once there were three competing networks, now there is a multitude within and beyond the televised bandwidth. If the mission of the art museum is to tell the story of art, then today, there are such a multitude of stories... let us consider that the art world today is so large, that the museum in the legacy of its configuration is currently incapable of doing its job, which is to tell the story of art. How can the museum evolve? How can it be the multiverse that can reflect the one we are living?

Maybe the fine art museum should emulate YouTube?

Opening Sunday Friday

(UPDATE: Mr. Ginzel's students must have got this wrong...)

December 4, 2013

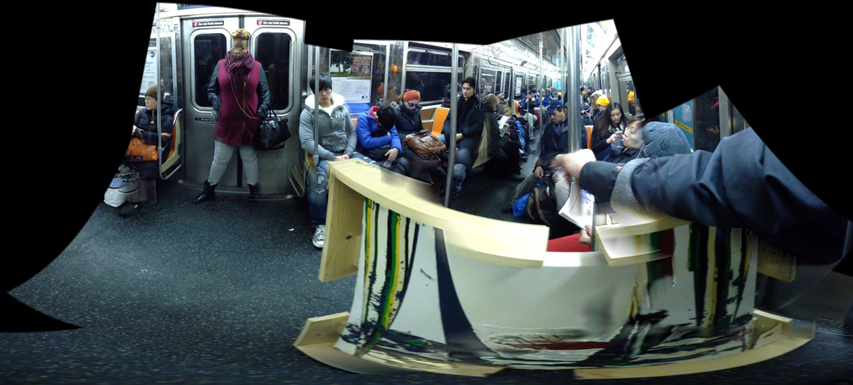

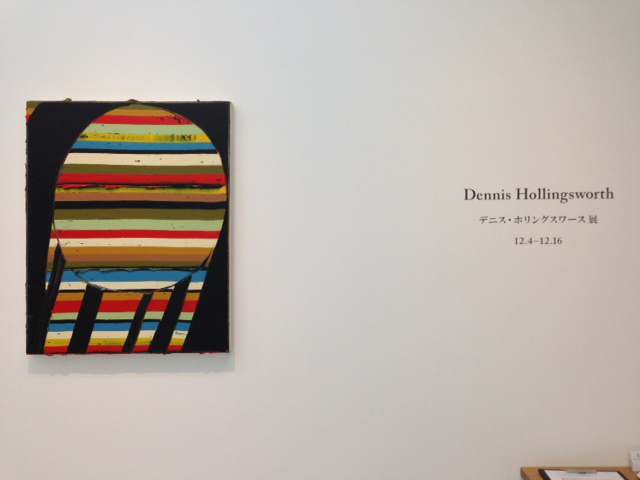

Installation Views: TKG Hikarie, Shibuya Station, Tokyo

My show has opened at 8/ ART GALLERY in Shibuya Hikarie in Tokyo, these are some of the installation shots.

I am grateful to know and work with Tomio Koyama, the team at Tomio Koyama Gallery have been fabulous and excellent all throughout the process. They asked me what my thoughts were about the installation plan, I sent them some drawings and they ran with them.

Here they are after the fold, I think that they will give a sense of the layout and one's mind can make the SketchUp drawings more vivid after seeing aspects of the actual space above..

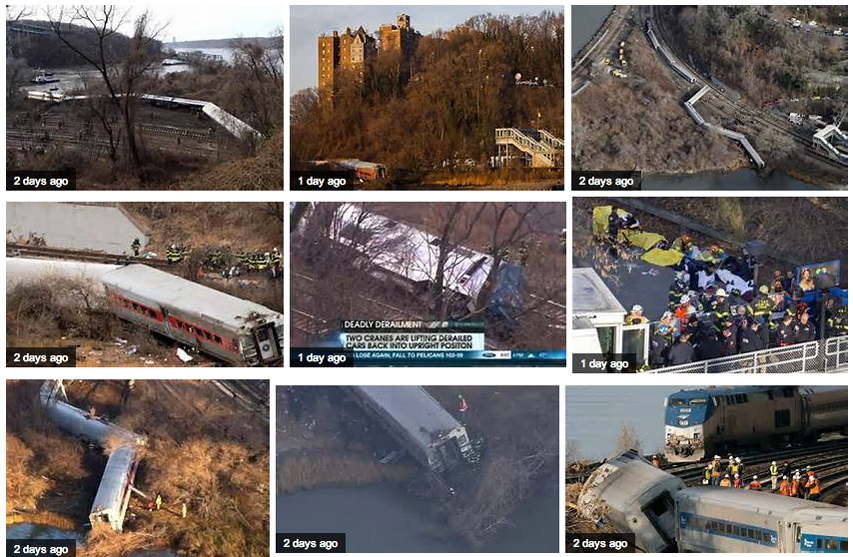

Who is in charge of the clattering train?

The driver was asleep on the clattering train...

[Major MARINDIN, in his Report to the Board of Trade on

the railway collision at Eastleigh, attributes it to the

engine-driver and stoker having "failed to keep a proper

look-out." His opinion is, that both men were "asleep, or

nearly so," owing to having been on duty for sixteen hours

and a-half. "He expresses himself in very strong terms on

the great danger to the public of working engine-drivers and

firemen for too great a number of hours."--Daily Chronicle.]Who is in charge of the clattering train?

The axles creak, and the couplings strain.

Ten minutes behind at the Junction. Yes!

And we're twenty now to the bad--no less!

We must make it up on our flight to town.

Clatter and crash! That's the last train down,

Flashing by with a steamy trail.

Pile on the fuel! We must not fail.

At every mile we a minute must gain!

Who is in charge of the clattering train?Why, flesh and blood, as a matter of course!

You may talk of iron, and prate of force;

But, after all, and do what you can,

The best--and cheapest--machine is Man!

Wealth knows it well, and the hucksters feel

'Tis safer to trust them to sinew than steel.

With a bit of brain, and a conscience, behind,

Muscle works better than steam or wind.

Better, and longer, and harder all round;

And cheap, so cheap! Men superabound

Men stalwart, vigilant, patient, bold;

The stokehole's heat and the crow's-nest's cold,

The choking dusk of the noisome mine,

The northern blast o'er the beating brine,

With dogged valour they coolly brave;

So on rattling rail, or on wind-scourged wave,

At engine lever, at furnace front,

Or steersman's wheel, they must bear the brunt

Of lonely vigil or lengthened strain.

Man is in charge of the thundering train!Man, in the shape of a modest chap

In fustian trousers and greasy cap;

A trifle stolid, and something gruff,

Yet, though unpolished, of sturdy stuff.

With grave grey eyes, and a knitted brow,

The glare of sun and the gleam of snow

Those eyes have stared on this many a year.

The crow's-feet gather in mazes queer

About their corners most apt to choke

With grime of fuel and fume of smoke.

Little to tickle the artist taste--

An oil-can, a fist-full of "cotton waste,"

The lever's click and the furnace gleam,

And the mingled odour of oil and steam;

These are the matters that fill the brain

Of the Man in charge of the clattering train.Only a Man, but away at his back,

In a dozen ears, on the steely track,

A hundred passengers place their trust

In this fellow of fustian, grease, and dust.

They cheerily chat, or they calmly sleep,

Sure that the driver his watch will keep

On the night-dark track, that he will not fail.

So the thud, thud, thud of wheel upon rail

The hiss of steam-spurts athwart the dark.

Lull them to confident drowsiness. Hark!What is that sound? 'Tis the stertorous breath

Of a slumbering man,--and it smacks of death!

Full sixteen hours of continuous toil

Midst the fume of sulphur, the reek of oil,

Have told their tale on the man's tired brain,

And Death is in charge of the clattering train!Sleep--Death's brother, as poets deem,

Stealeth soft to his side; a dream

Of home and rest on his spirit creeps,

That wearied man, as the engine leaps,

Throbbing, swaying along the line;

Those poppy-fingers his head incline

Lower, lower, in slumber's trance;

The shadows fleet, and the gas-gleams dance

Faster, faster in mazy flight,

As the engine flashes across the night.

Mortal muscle and human nerve

Cheap to purchase, and stout to serve.

Strained too fiercely will faint and swerve.

Over-weighted, and underpaid,

This human tool of exploiting Trade,

Though tougher than leather, tenser than steel.

Fails at last, for his senses reel,

His nerves collapse, and, with sleep-sealed eyes,

Prone and helpless a log he lies!

A hundred hearts beat placidly on,

Unwitting they that their warder's gone;

A hundred lips are babbling blithe,

Some seconds hence they in pain may writhe.

For the pace is hot, and the points are near,

And Sleep hath deadened the driver's ear;

And signals flash through the night in vain.

Death is in charge of the clattering train!Anonymous

(Link.)

Modernity and Churchill, part I

I'm fortunate to be able to listen to audiobooks and podcasts as I work.

In The Last Lion by William Manchester, volume I, we follow the early life of Winston Churchill through Cuba, India, the Sudan, South Africa and then into his freshman years as a politician. All of this action occurred during the last decade of the 19th century and during the narrative, images of art history flashed in my head: Van Gogh, Lautrec, Cézanne... As Churchill became the First Lord of the Admiralty and the First World War was unleashed, images of Picasso and Braque paraded alongside.

Churchill's biography is hinged between the Victorian epoch and the birth of the Modern era. In art history, we learned that as the Industrial Revolution revved up, inventions and innovations altered everyone's life to the degree that existing conventions had to be scrapped and for a time, redrafted and redrafted until any hope of a stable new order was lost completely. Revolution succeeded revolution and art movement succeeded art movement with such acceleration that eventually the hope of the codification of a definitive and coherent art theory was lost completely at the end of the 20th century.

As I listened to the unfolding narrative of WWI, I realized with clarity something that I had known before but only dimly so: that art history should be taught in tandem with world history. The context of world events is a vital key to understanding the force that compelled the unfolding story of Western Art. The explosion of the modern cannot be understood without an appreciation of the impact of the discovery and implementation of electricity, communications both wired and wireless, the mechanization of transport and production, photography and flight. For example, Malevich conceived of abstraction after contemplating the impact of aerial photography, such was the impact of the disappearance of the horizon as the camera lens first panned earthward from the clouds.

The concept of the nation state was born in the middle of the 19th century and as the sun set on empire, Britain devolved their imperial possessions at the same time that the newly born nations of Germany, Russia and Japan tried to lay their claims to empire status. All armies had to do from time immemorial was to manufacture arms, whether swords or rifles, minimally train conscripts mobilized from their subject population and hurl their mass against their foes. The American Civil War (flash: John Singer Sargent) first indicated the modernization of arms in the use of better manufacturing that delivered better accuracy at longer range. This lesson wasn't absorbed by the time of WWI such that armies became deadlocked in trenches (flash: Beckman), casualties machined by automated guns. War compels an existentially driven innovation and imagination was trapped in the trench lines, able only to create technology that killed in static warfare, such as poison gas. (flash: Otto Dix.) It was Churchill that tried to innovate tank warfare, to employ airpower, and ultimately to try to overcome the deadlock by attacking Germany's rear via the Dardanelles --only to be foiled by a timid captain who didn't guess that the Turks were almost out of ammunition. It was Germany in WWII that developed the idea of dynamic attack (flash: Boccioni) with mobile warfare, the blitzkrieg, attacking countries whose minds were yet fixed in the mindset of the previous epoch, still too horrified by war to defend themselves (flash: Balthus) from others who were not.