October 25, 2014

Review Panel 10/24/14

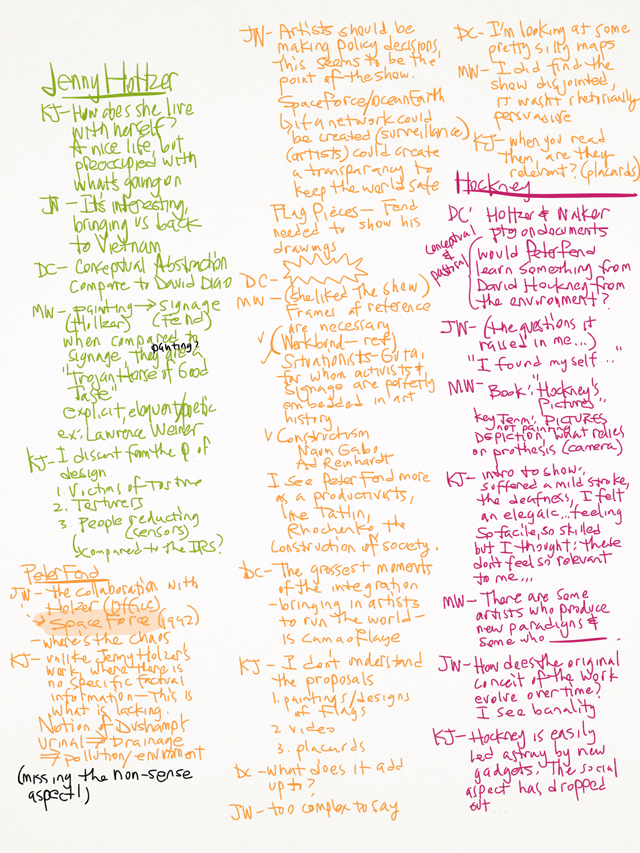

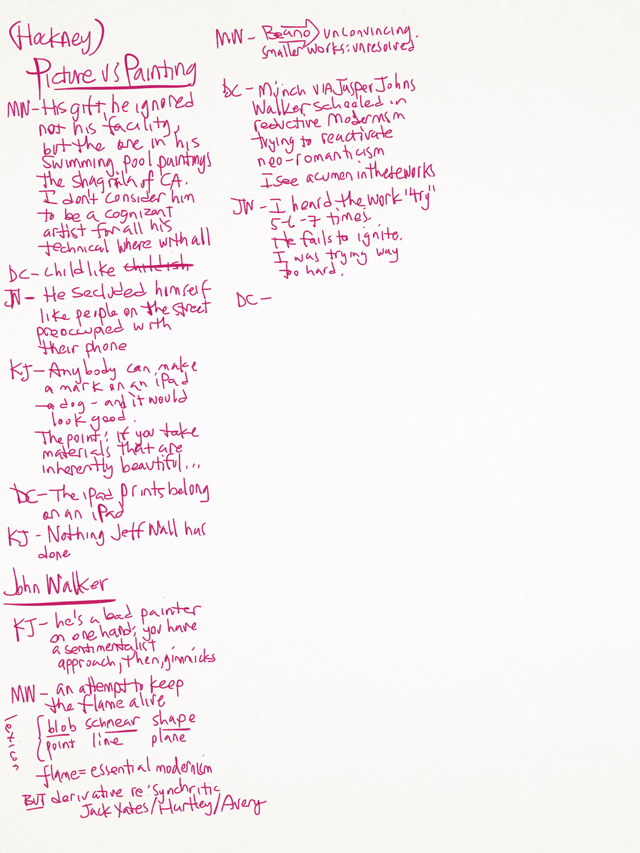

These are notes from this week's National Academy Review Panel, moderated by David Cohen, talking about four shows in NYC this month, Jenny Holzer, Peter Fend, David Hockney and John Walker.

I enjoy listening to the Review Panel, less for the specific judgements about the art in question and more to see the critics in person, to see how they think on their feet, their character and wit. David Cohen is a delight. In this panel I could appreciate how Joan Waltemath consistently and sensitively measures how much an artwork "throws one back upon oneself", of the formidable intellectual wattage of Marjorie Welish, of the strange psychedelic curmudgeon-ish-ness of Ken Johnson. Revelations, all.

Usually, the Panel takes on each show sequentially, but I think that this time it might have been better to have heard the critique take them on all at once. You have two pairs of exhibitions, each alike in interesting ways: Holzer/Fend and Hockey/Walker. I saw all four as grizzled veterans, and yet there are stark differentials in each in terms of public acclaim and perceived accomplishment. Curiously, the younger of the pairs had aged faster of the two. Of all four, questions rose to my mind of what constitutes suppleness in art and what survives the passage of time. Ken Johnson slyly disparaged the selection as a "pastorale versus agit-prop" (this characterization is the best my memory will serve of his words), but I think he missed what could have been a much more interesting critical approach.

By contrasting the (perhaps) now all-too-familiar painting versus conceptualism axis, they could have talked about how political/conceptual art stresses subject over media and whether in these cases, they succeed or not. Is the art experience topicality (conceptuality) itself, or does art have another locus entirely? (An audience member suggested this, saying that art must first make us feel before anything else.) What happens when political agendas change with the times and when is it timeless? Can the gold standard of Goya's Third of May apply to Holzer's indictment of the second Gulf War and if so, how would her show at Cheim and Read fare in comparison? Does painting endure, indeed, and if so, how does happen? When is conceptuality rich or complex enough to qualify as art material? What is the difference between subject and concept? What is the difference between artist and subject and can one manipulate the other? When is the medium, and when is it not, the message?

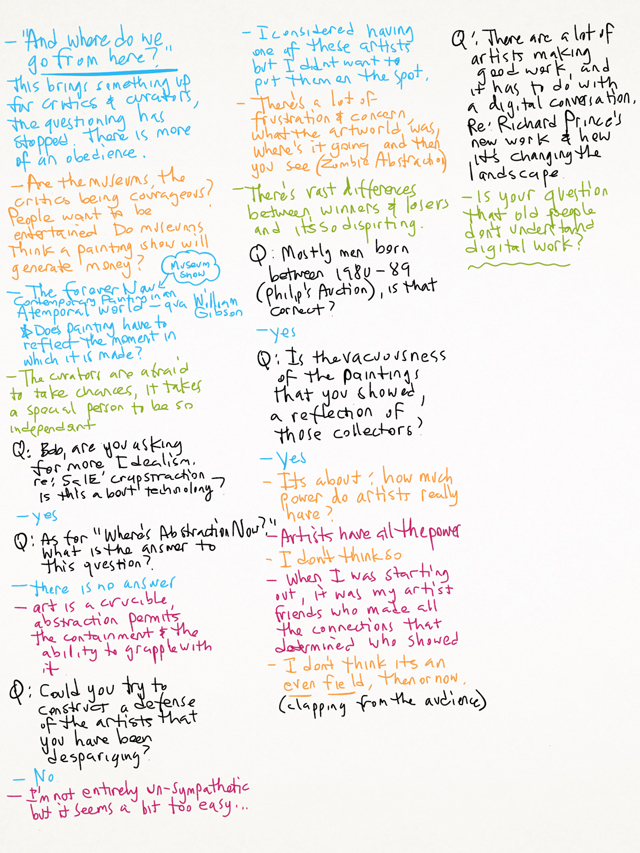

Where do we go from here?

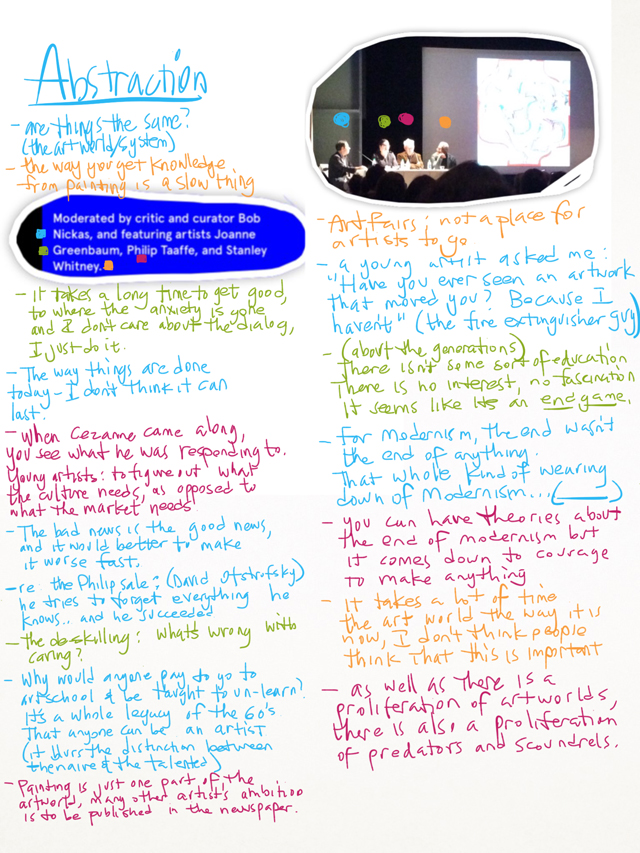

These are notes from last Thursday night's talk at the Jewish Museum, What's at Stake for Abstract Painting Today - and Where Do We Go from Here?, moderated by critic and curator Bob Nickas promised to be interesting, drawn in not only by the participation of friends Joanne Greenbaum and Stanley Whitney but principally by the title. I earnestly wanted to hear their thoughts about such a difficult subject as this, the future of abstract painting. How would Nickas frame it? Would they attempt an elementary definition of abstraction to clear the deck, and could they map out the territories of abstraction and define which aspects are well mapped, which are over-mapped and where is yet the terra incognito of abstraction?

Instead, Nickas steered the conversation towards a one sided critique of current events now dominating the headlines via the recent auctions, the most notable being the Philips Under the Influence, where extremely young artists' careers have been supercharged by rabid speculation, instilling fears of a developing financial bubble in the art world, not to mention a distorting influence on art history. Indeed, this topic has been on everyone's mind recently, and no doubt a debate about it would be a welcome event. But that night's panel discussion needed the presence of some of these younger artists in question, not to mention some of the collectors and dealers who are involved in the dynamic. Have you heard of the Ideological Turing Test? It's call to empathy towards one's intellectual opponent. Such a precaution requires us to first state your interlocutor's position as good or even better or more vividly than they can, before you start to dismantle it. It would have been good to have heard from the devil's advocate that night.

The artists who comprised that night's panel did their best to temper the arc of the discussion. At one point, Nickas brought up the prospect of a museum exhibition set to open in the near future and asked their opinion about it. The artists on the dais all responded as politely as they could, saying variations along the line: "...when I see it, I'll tell you what I think". As for the question of what's at stake for art today, the artists Greenbaum, Taaffe and Whitney all offered wisdom despite the difficult terrain charted by the moderator.

"Where do we go from here?" indeed.

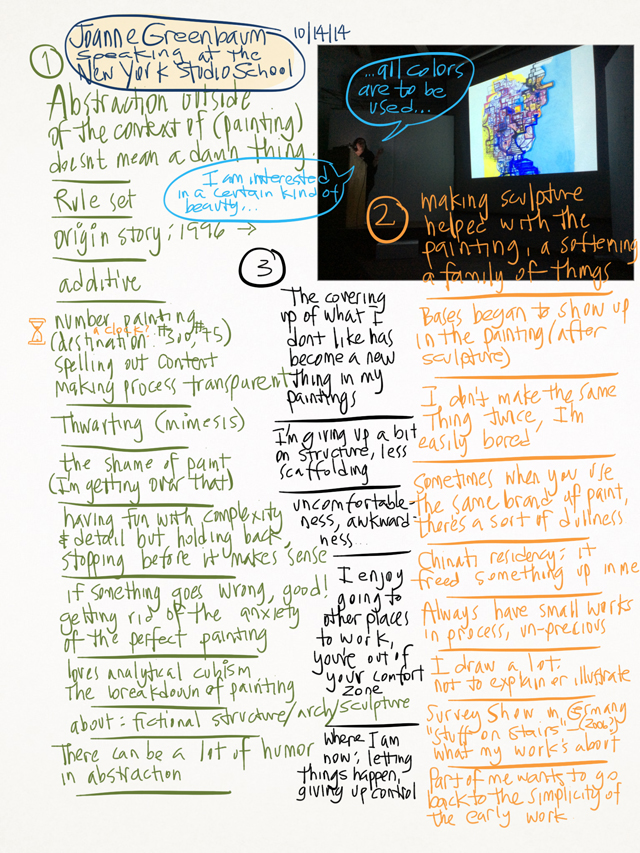

October 15, 2014

Joanne Greenbaum at the NY Studio School

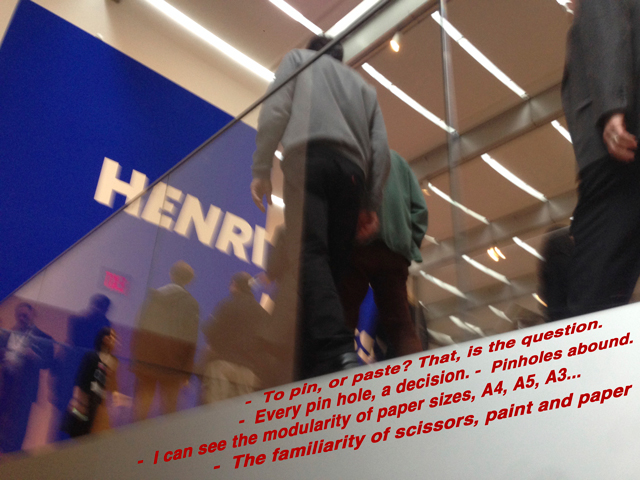

I took notes as Joanne Greenbaum gave a talk about her paintings at the New York Studio School, the birthplace of the Whitney Museum.

October 14, 2014

October 8, 2014

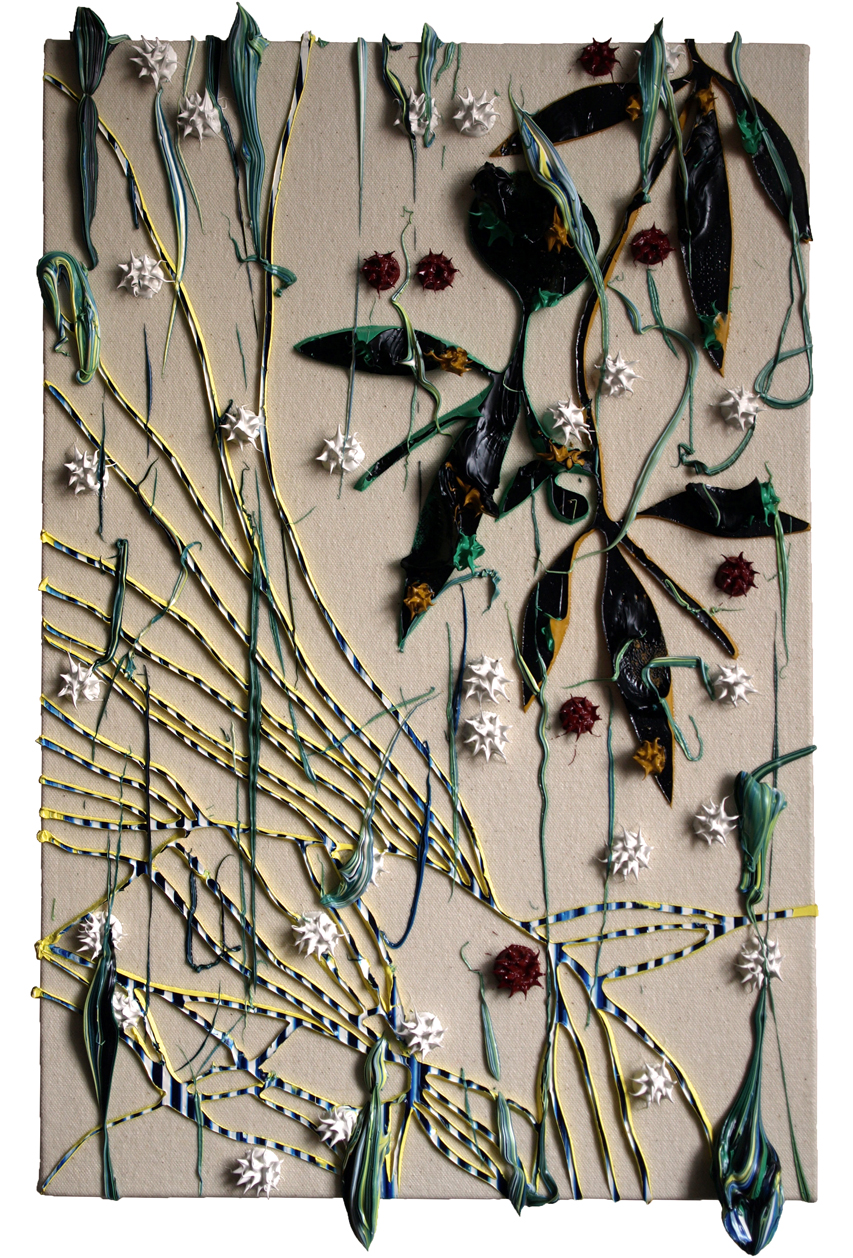

such crooked timber

such crooked timber

2014

#470

18"x12"

I Spy With My Eye...

From my apartment, I can see a tower in construction, friends tell me that it's midway through the process. A friend summoned this video for me recently:

Broken Glass Everywhere

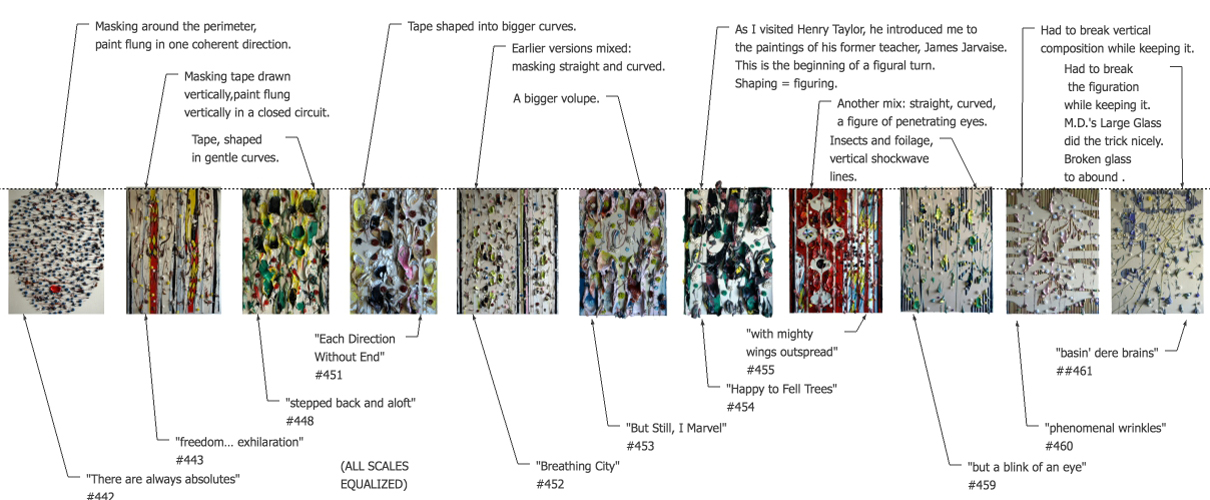

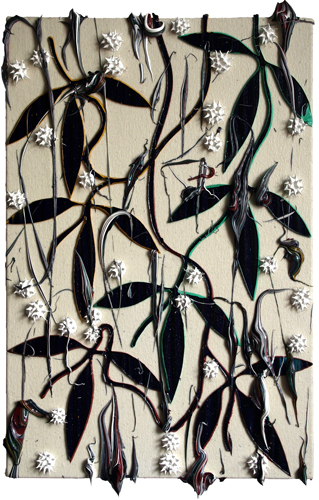

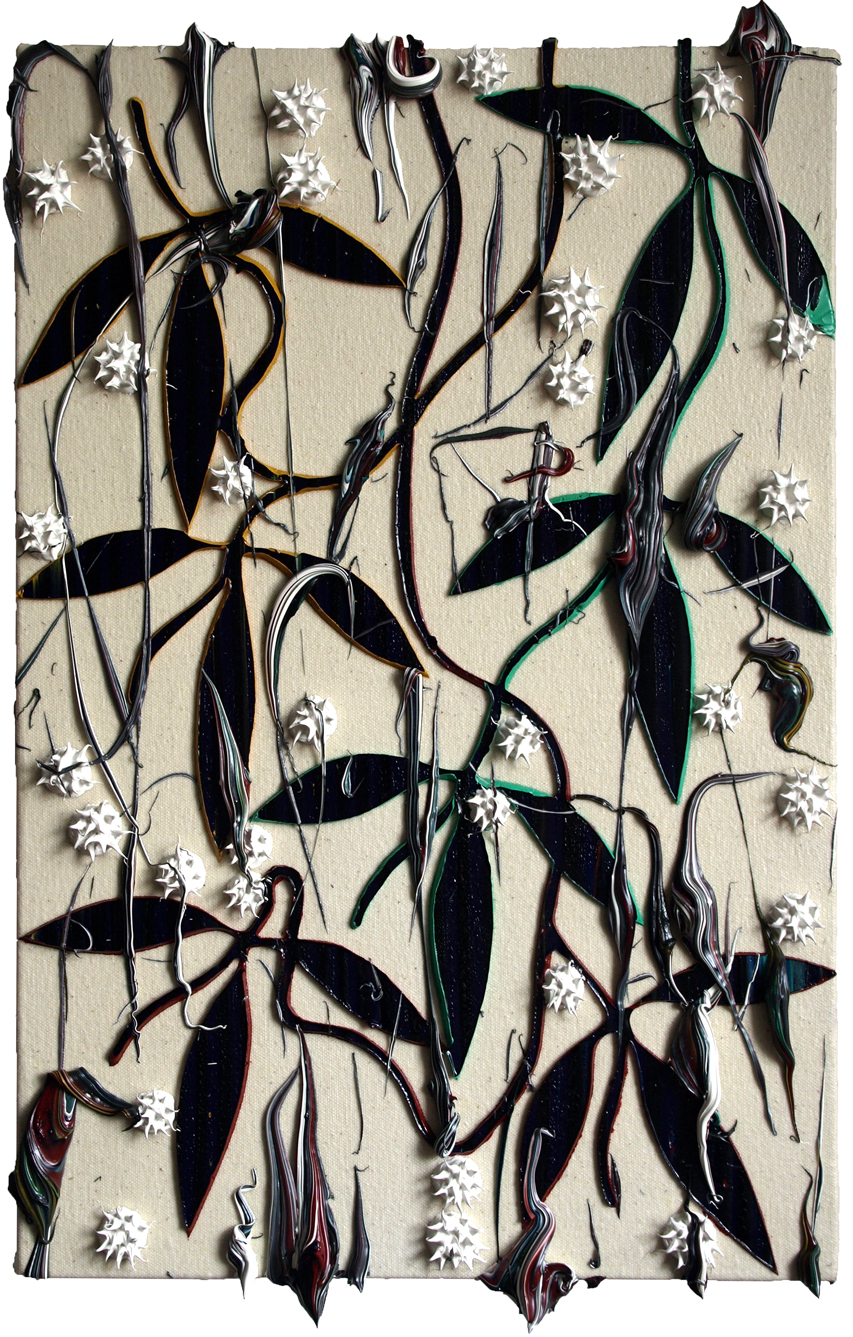

The past cycle of paintings describes an arc of development from the instrumentalization of masking (as in masking tape) and directed projectiles of paint (paint, the remainders scraped off tools and tape, reserved aside throughout the process and then flung back on the canvas at a final stage, a closed system of paint deployed). I often refer to the movement from painting to painting as tacking, in the manner of sailboats navigating into the wind. Masking began as vertical pulls of tape, then shaped into volupes (volupté, the quality of being voluptuous or sensual), mixed and mashed, later cut into figures after seeing the work of James Jarvaise, forests grew, teeming with insects and then I needed to break that egg. "Breaking the egg" is the phrase I use to question one's project. I usually visualize this as small cracks, because a huge break will scramble your egg. Small breaks require healing fissures, a tectonic movement, bones cured stronger than before.

So one day, it was time to break the influence of Jarvaise, and as I was flipping through Transgression, The Offenses of Art, I seized upon the illustration of Marcel Duchamp's Large Glass, an image of a broken image, a perfect motif.

And then I noticed broken glass abounding. Suddenly, it's everywhere.