June 29, 2015

June 16, 2015

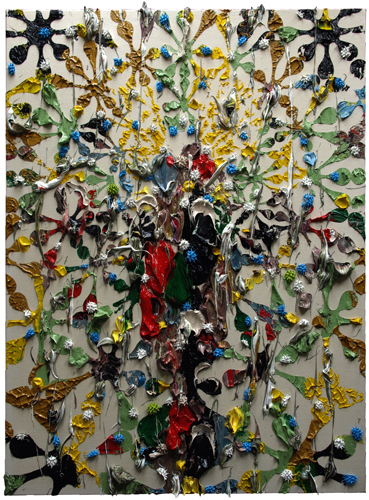

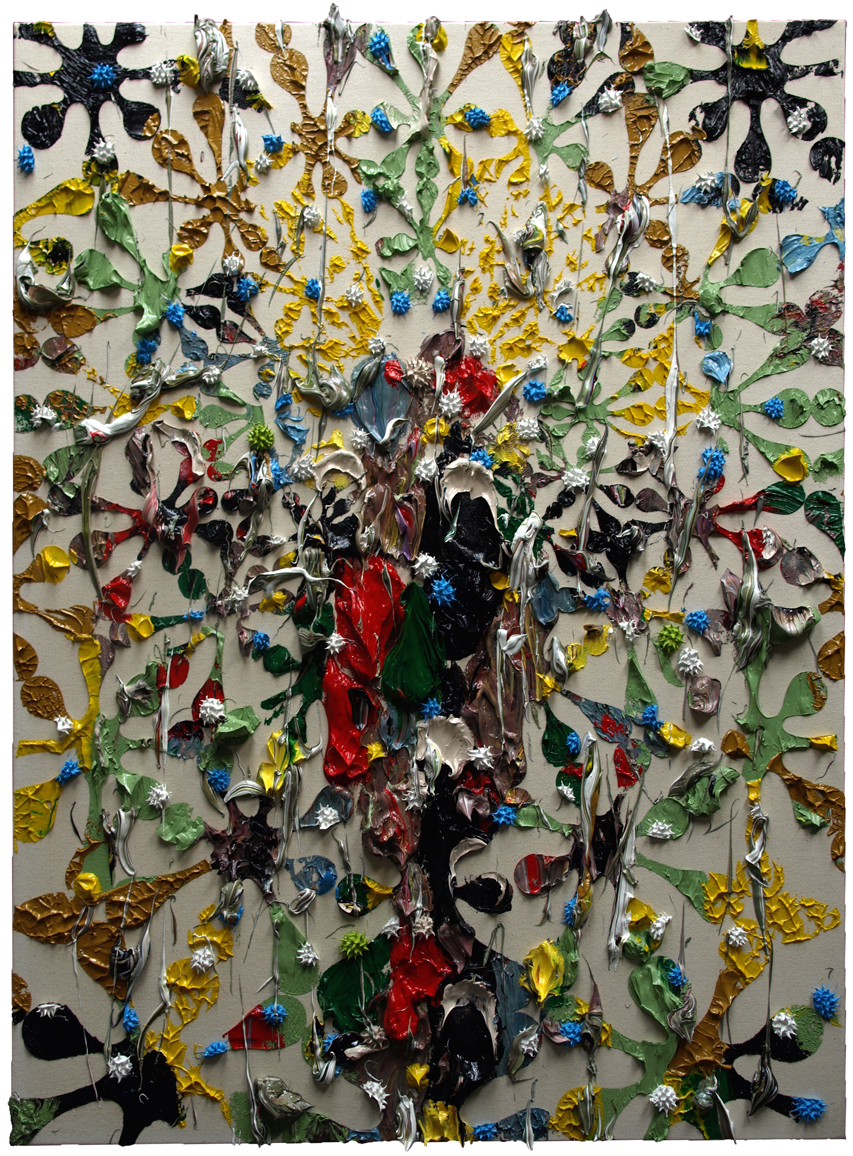

For Christ's Sake

For Christ's Sake

2015

#494

60"x48"

Oil on Canvas

Oh, For Christ's Sake

Jonathan Jones flayed Bacon's painting in his review of the exhibition Francis Bacon and the Masters at the Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia in a guardian review last April of this year, Francis Bacon and the Masters review -a cruel exposure of a con artist. With paragraphs like this, this review is indeed a brutal takedown:

Yet Bacon and the Masters is a massacre, a cruel exposure, a debacle. Bacon's paintings are mocked, his talents dwarfed. The jaw-dropping masterpieces by the likes of Picasso, Titian and Rodin that so nearly make this show five-star unmissable also, to my dismay, to my shock, make Bacon seem a small, timebound, fading figure.

I'm less motivated to write about this show when it comes to the takedown of a modern master and more taken by the lead image headlining the article, side by side crucifixions by Bacon and Cano. It's too bad that I'll miss seeing the exhibition, it would be interesting to see if there is more historical continuity in the selection of subject and motif throughout the centuries.

My first thought instead was this: Did Francis Bacon believe in Christ?

I don't think so. I suspect that he was motivated by the recurrent subjects of art history and his abiding concern prefigured the curatorial angle of this show. Francis Bacon compared himself to the icons of art history and he wanted others to see him in this way as well. Compare and contrast for yourself the Wikipedia descriptions of the Pope Innocent X for Velázquez and Bacon, you might understand as I do, the depths of one and the shallows of the other. But what would be shallow in the dimension of civilizational impact and religious depth, there's plenty of profundity in a shear visceral grinding intensity that can be grounded in a crucifixion transference and expiation of soul destroying sin or the Papal agent thereof. No, I don't blame Bacon for fixing onto the surface of his subject, he is a creature of modernity after all. The surface of art will shimmer to the thickness of molecules in a few short generations, reflecting him in a surfeit of dimensions after all.

What of Jesus? Do I believe in him?

Well, the probability is strong to certain that he existed of course but I think that the odds drop sharply when it comes to the story of divinity incarnate. Ardent believers would probably protest the second assertion strongly, but I'd say that Jesus' existence is much, much more significant than a mere historical fact and even... even of the immanence of the singular deity (G-d) in the world. A thought like that would put me in the category of a deist in that I accept the existence of the creator on the basis of reason, as the prime linchpin of civilization, but I am cool to the idea of a supernatural deity who interacts with humankind. The most persuasive Judeo-Christian idea is the one called Logos, of reason, of its divine origin, and its natural manifest incarnation. I'm proposing (reasserting actually, since this needs be done in our day and age) that freedom is vital to civilization and the prime narrative of the story is central to the Torah/Old Testament, of the gift of freedom by G-d to mankind. It is the Christian franchise of this narrative (and the Deism beyond that followed) that extends what has always been implicit in Judaism, explicitly to the world at large.

What probably motivated Bacon to paint the crucifixion was the passion of Christ, the suffering and death of Jesus. It must be the extremity and intensity of experience that attracted Bacon, which seems to me to be a species of attraction that drew Mel Gibson to make The Passion of the Christ. Both artists seem to revel in suffering, but in a kind of out of the body POV, a kind of remove, a distance from the true horror to be found at the core. Real suffering is when one loses sight of redemption, the kind of which the Justines of the world have experienced. For example, there are women in ISIS Iraq at this exact moment who have been sold and resold into a rapist slavery several times over, who have no hope of rescue or redemption. Now, this is true suffering, ladies and gentlemen.

When I first saw Gibson's movie, I felt that he had barely scratched the surface of crisis. Beyond the movie, there is a problem about the portrayal of Christ as a man certain of his divine identity, a G-d incarnate would implicitly know of his own indestructibility and even the imagination of any mere mortal would be insufficient to leverage the level of wretchedness required to expiate the collective sin of humanity in the dimensions of the Christian narrative. Yes, Jesus famously cried "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?", and more of this meltdown of doubt salted throughout the story of Christ would be much more resonant. The schizoid split between the divine and mere mortal is the precise origin of the pain of this singular suffering, of the kind best illustrated by Nikos Kazantzakis' Last Temptation of Christ.

So, for as much as I admire Francis Bacon, I don't buy the usual take on the dramatic premise of the subjects of his paintings. A significant painter, consequential, singular and worthy of all the praise heaped upon his oeuvre, yes. At worst, the pain he dramatizes seems more akin to my mind & eye on one level to that of an administrator than that of a recipient and on another level, a superficial turn of fashion, no different in significance or intensity than a punker's torn, scuffed and safety pinned t-shirt. At best, Bacon's passion is probably driven by a crisis of identity, a keenly felt pustule of which has swollen in popular culture in recent years.

June 14, 2015

June 8, 2015

June 5, 2015

#TBT: The Opening

Stephanie to the left, Peter Hionas at the door. Shirley Jaffe's painting center, and my painting to the right.

Rebecca Smith's sculpture center, my "Juliet" to the left and Shirley Jaffe to the right. A great vantage point, a cascade of ochre.

David Rhodes' vertical painting to the left, Marina Adam's painting mounted high on the wall.

This shot was from Monday, Peter Hionas and Jill Levine to the right. Jill's painted sculptures are center/past and left/present, Joan Waltemath's subtle grid paintings to the right.