August 31, 2015

Nutshell

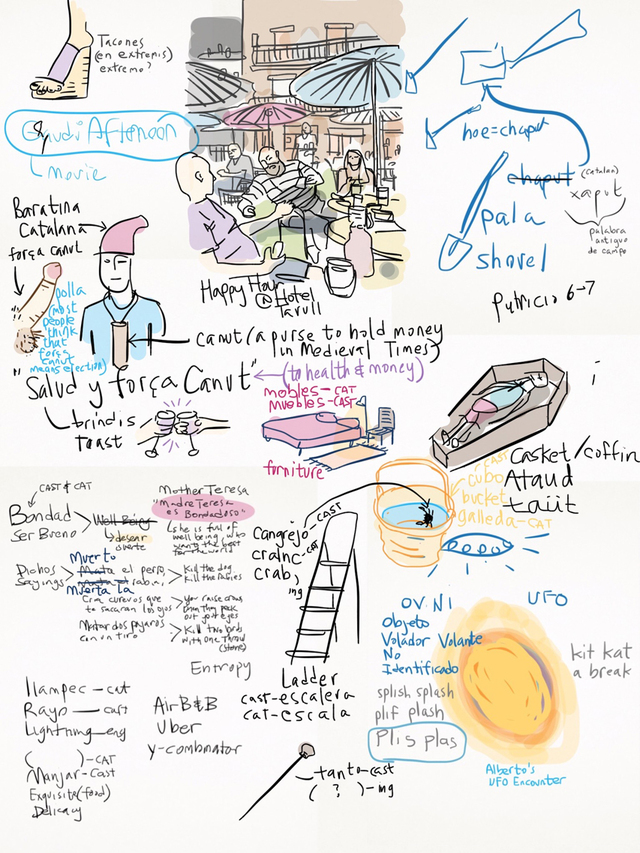

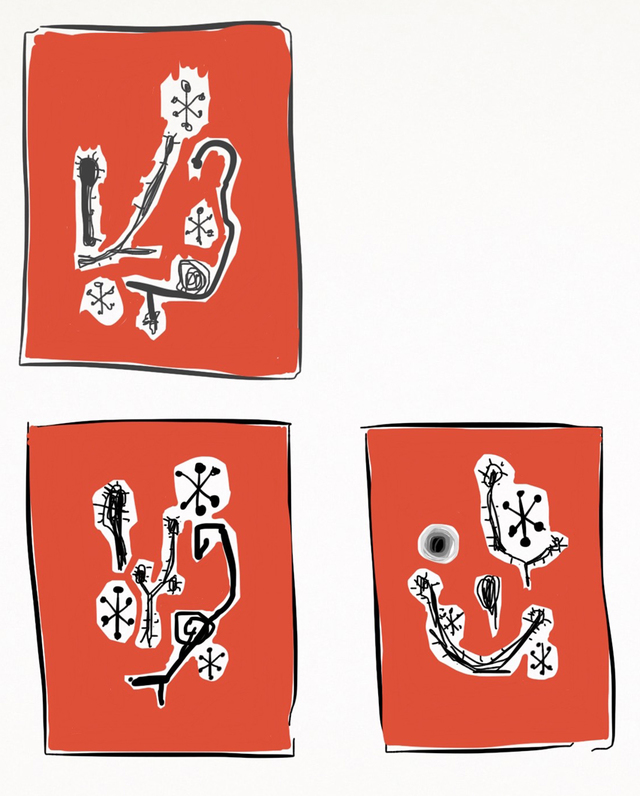

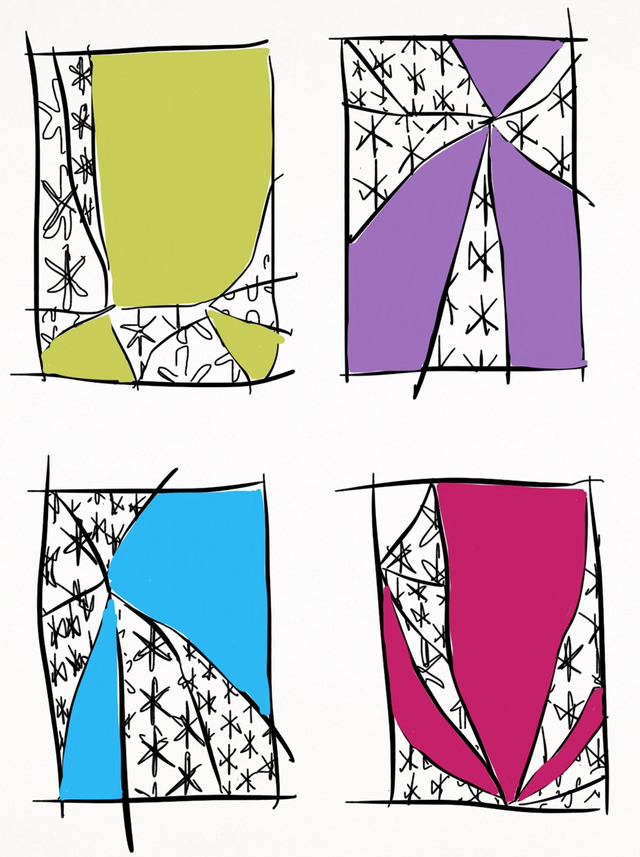

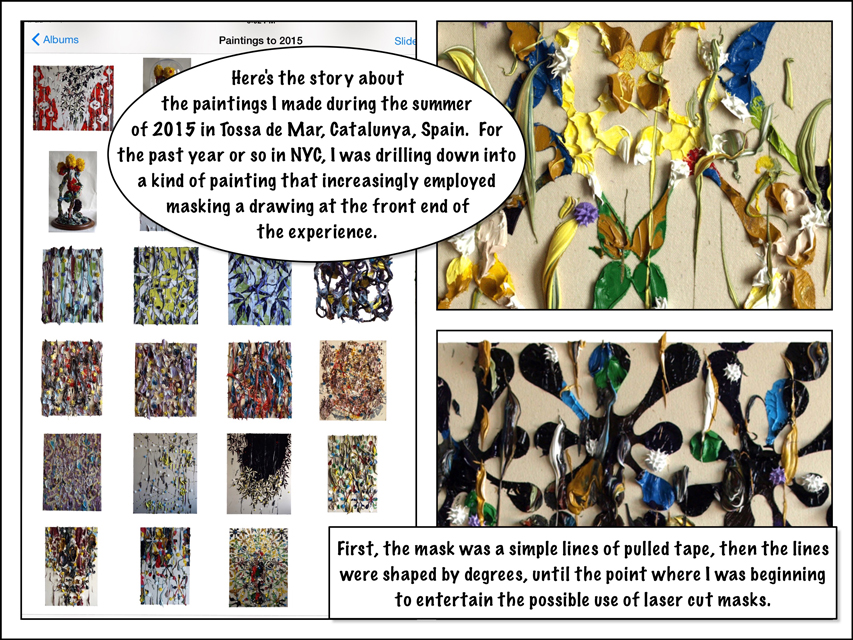

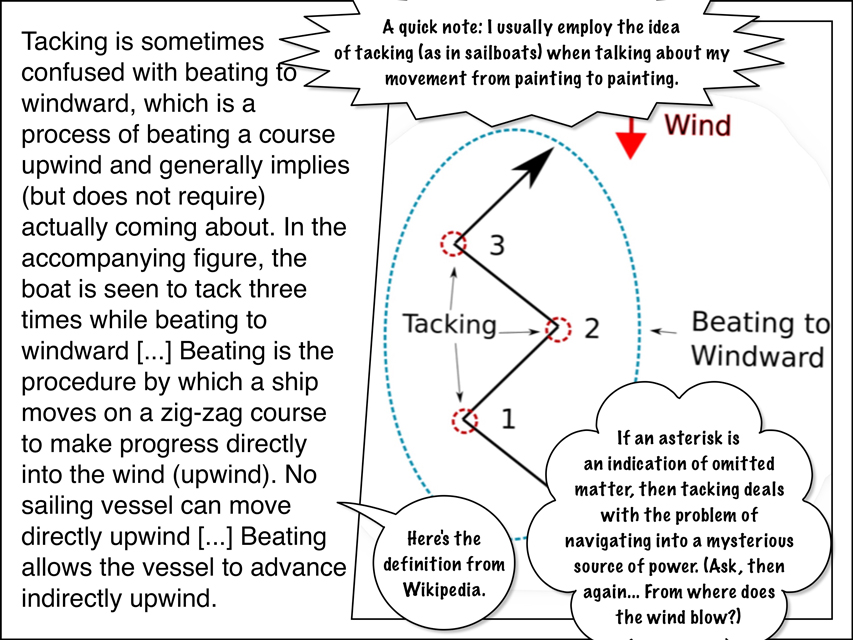

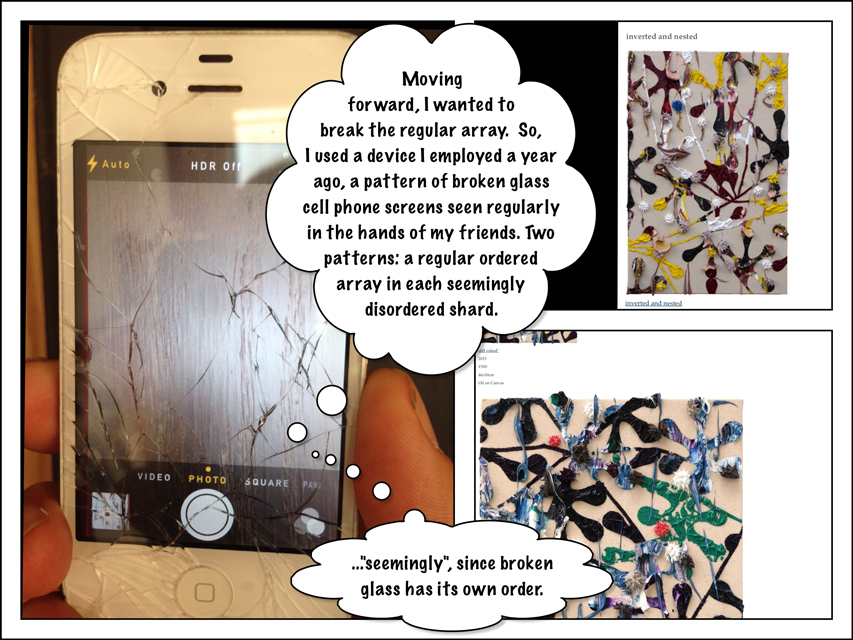

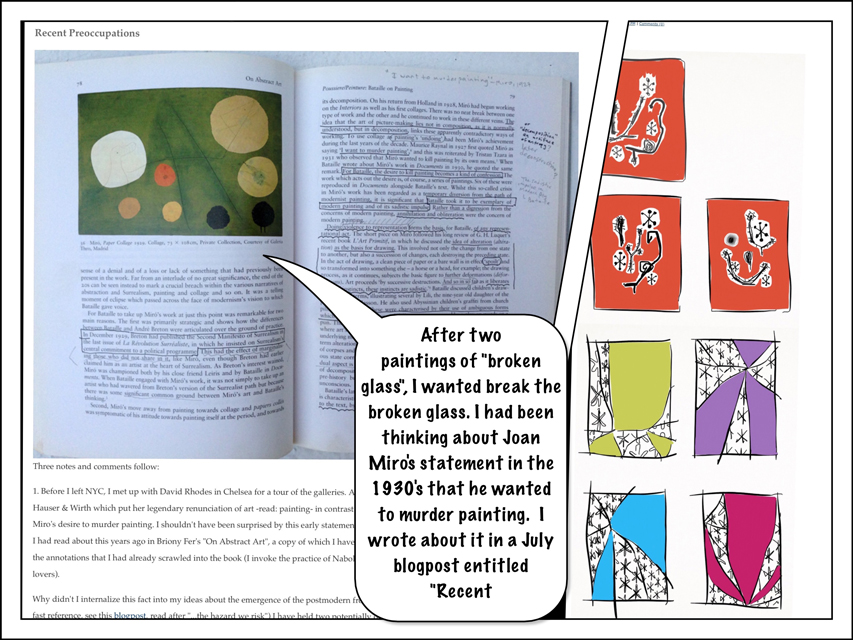

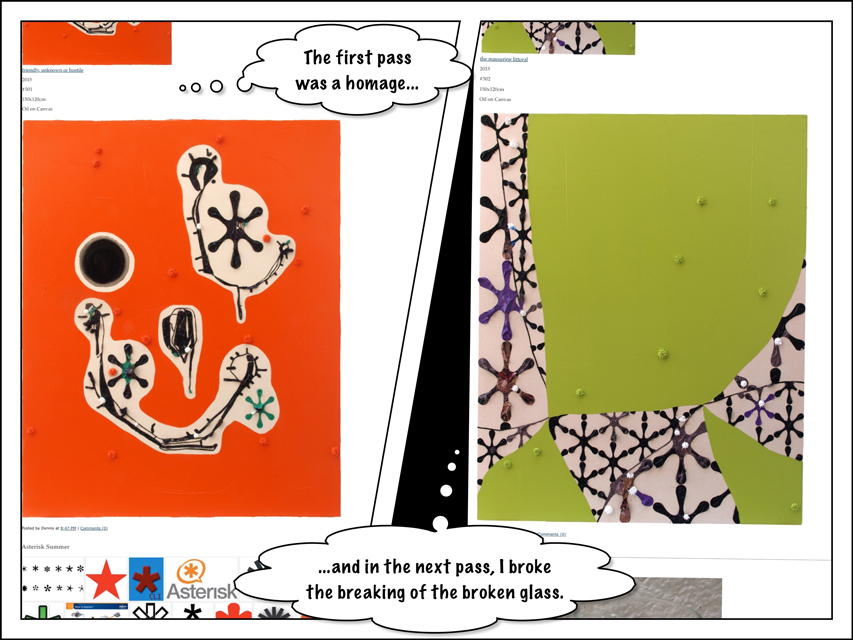

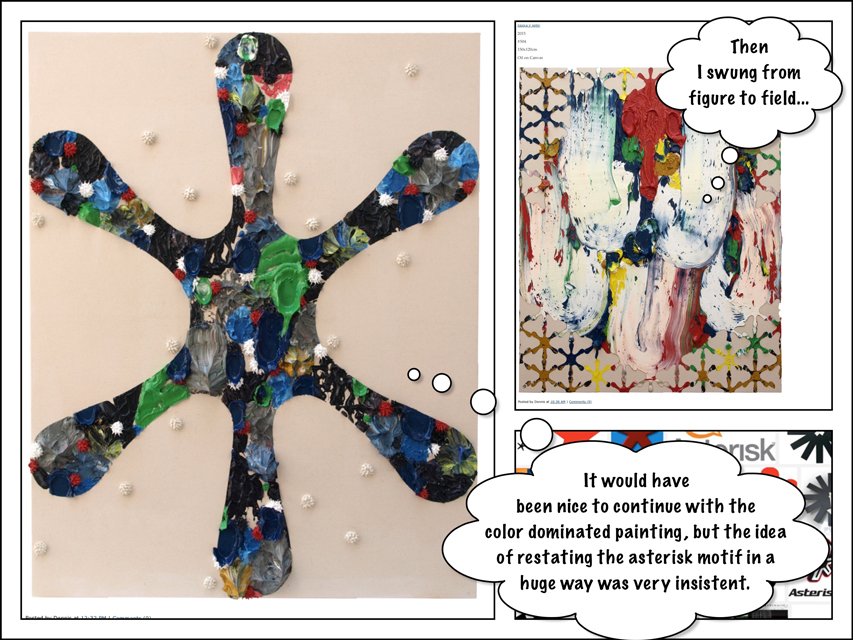

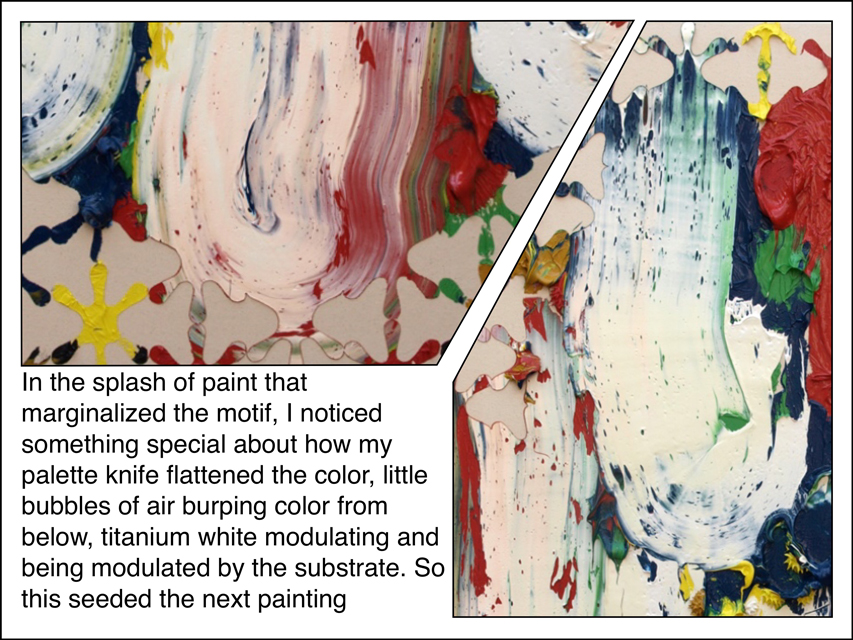

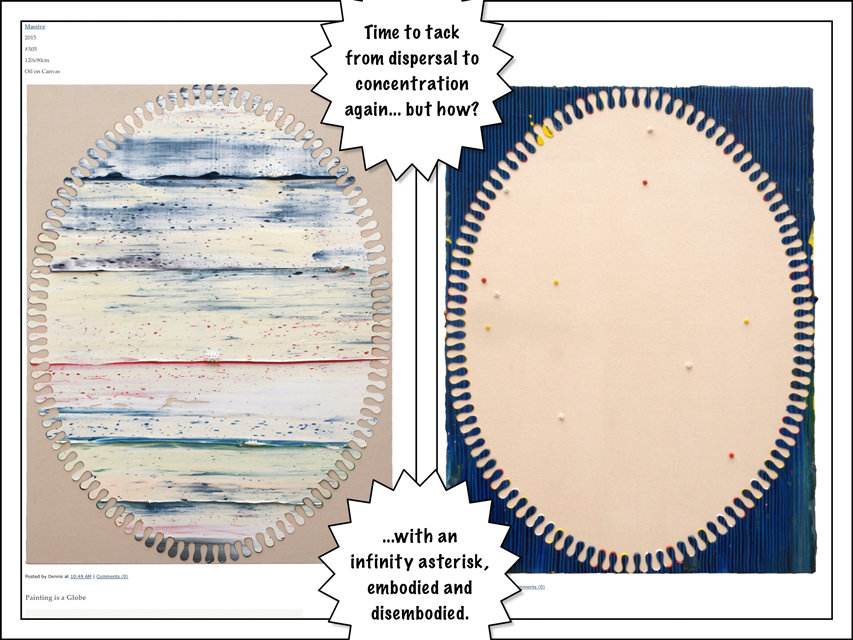

There is a train of thought that I wanted to convey to you, dear weblog diary reader, regarding how each painting provokes the next in my studio. Of all the ways that I could summon to get this across to you, I chose an app in my iPad (Strip Design) to get this done and done it was, "Pim Pam Poom", as we say in Spain. I hope you are intrigued, and if you are, please scroll through the archives (here, here and here to start) to fill in some blanks.

August 30, 2015

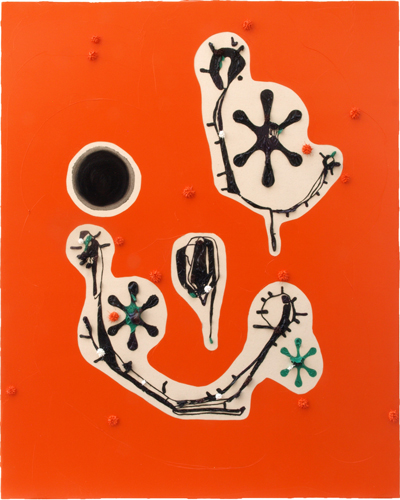

abide or endure or suffer

abide or endure or suffer

2015

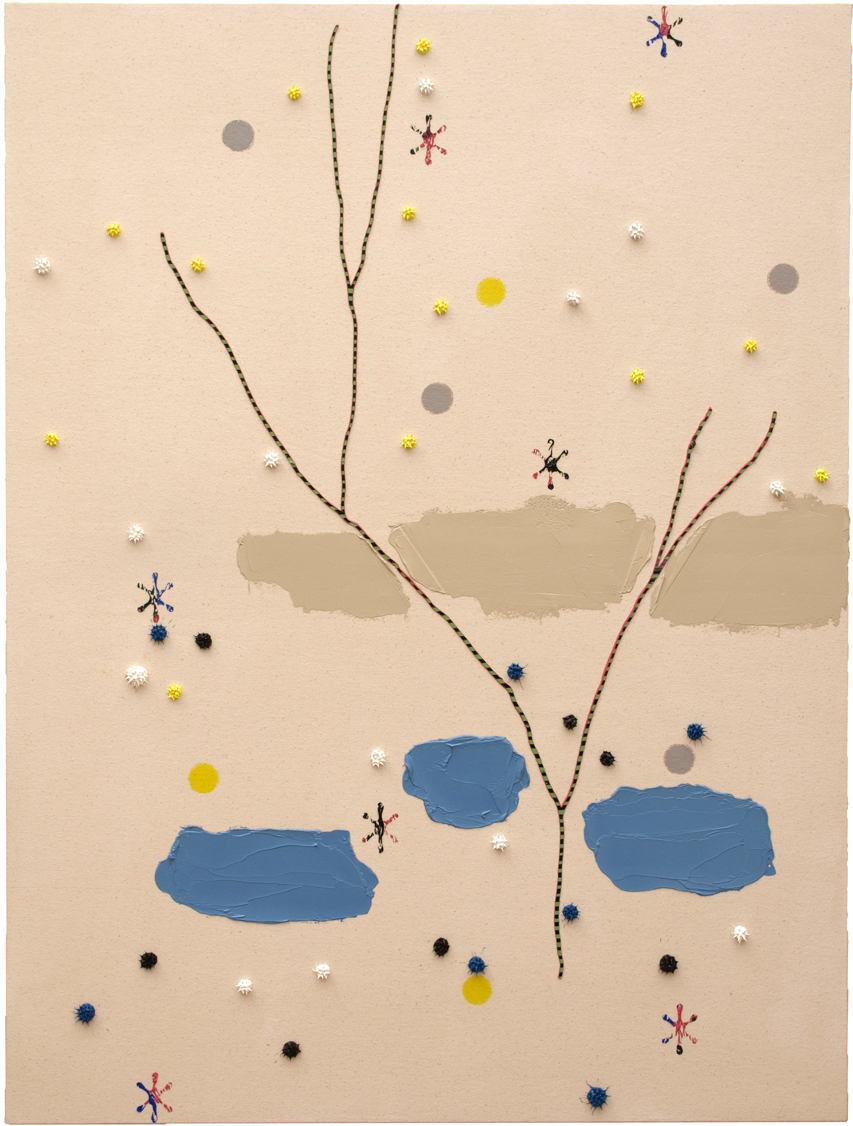

#508

92x76cm

Oil on Canvas

August 27, 2015

Friends visiting Tossa

Paula Masters flew in from Dallas to take the Mediterranean air.

August 25, 2015

Malevich's Turn

In blogposts such as The Kasimir Malevich Spectrum and "Where there is freedom, there is happiness.", I puzzle over the sudden bloom of avant guard in revolutionary Russia at the beginning of the turn of the 20th century, how was it that Malevich and his circle was motivated and able to surge as they did in abstract art and what exactly happened when Malevich turned from the apparent purity of absolute abstraction to his apparent retrograde representation afterwards. Most people that I talk to about this take it as a fact that Malevich was coerced by Stalin, but questions lingered in my mind: Was there a direct threat expressed by Stalin to Malevich? How was it that Malevich was able to survive at all? Was there a hidden program that Malevich was expressing when he recuperated the peasant representations of his youth in his post-Suprematist days? Am I correct in my suspicions that Malevich scrambled the dates in his paintings and if so, why would he do this? These questions are still as yet for me unanswered. But much of the wellsprings of Russian modernism has been illuminated for me in John Batchelor's recent interview with Timothy Snyder, about his soon to be published Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning. I highly recommend listening to the audio link to the podcast. By the way, Timothy Snyder will discuss his new book at NYC's 92y on September 9th, 2015, I'm planning to attend.

Here are the schedule notes from John Batchelor's interview with Timothy Snyder in their entirety because the discussion links the events of the beginning of the 20th century with recent events in the 21st, a brilliant illumination. All bolded emphasis is mine:

Hour Four

Friday 21 August 2015 / Hour 4, Block A: Timothy Snyder, New York Review of Books; Housum Professor of History at Yale. His new book, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, will be published in September; in re: Edge of Europe, End of Europe The crisis of the European Union has two sides. One is political, about the lack of democracy within European institutions; the other is philosophical, about the erosion of Europe as a source of and home for universal values. The political crisis is on view in Germany and Greece. As we observe today, it never made sense to create a currency union (the Euro zone) without a fiscal union (a substantial common budget). A fiscal union would require more European democracy to legitimate the taxing and spending. When the Euro was established, the hope was that the common currency would create political solidarity that could foster European democracy; this simply has not happened. The Greek crisis has become a clash of multiple European democracies, in which the weak must bend to the strong. Greeks are not getting the policies they voted for; but then again Germans and other Europeans would not have voted, given the chance, to bail out Greece. Without a European budget, crises of this nature are inevitable; without European democracy all solutions will lack political legitimacy.The philosophical crisis is on display in Russia and the eastern borderlands of Ukraine. Ukrainians in 2013 demonstrated, in their revolution, a strong commitment to the idea of European integration. From the perspective of those who risked their lives on the Maidan, the central square in Kiev that was the center of the uprising, cooperation with Europe was essential for Ukrainian civil society to be able to mend the corrupt Ukrainian state. The essence and explicit purpose of Russia's war in Ukraine, on the other hand, is the destruction of the European Union as a universalist project that Ukraine could join. In its place, Moscow wants to establish a rival to the EU, known as the Eurasian Union. Rather than universal recognition of the legality of states and rights of citizens, the Eurasian project proposes a Russian hegemony of territories that Russian leaders regard as historically theirs, such as Ukraine. Its moral premise is that members of the European Union have abandoned traditional European culture (by which is meant religious, sexual, and political exclusivism) for "decadence" and that only Russia represents civilization.

Yet the Russian effort to break the Ukrainian state by military occupation and Eurasian propaganda has not, at least thus far, succeeded. Very few people in Europe would actually prefer the Russian model on display in Crimea and the Donbas--millions of refugees, a defunct economy, everyday violence, thousands of deaths, general lawlessness. On the other hand, since a large number of Ukrainians have been willing to take risks, suffer, and die in the name of Europe--even as the EU itself suffers a grave identity crisis--it makes sense to ask what they think they are working toward.

In the long reach of intellectual history, the encounter between Russian disintegration and European integration is something quite familiar to Ukrainians. The Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, less than twenty miles from the Russian border, was home to one of the thinkers who tried to set this long process in perspective. For George Shevelov (1908-2002), one of the great philologists of the twentieth century and a professor at Columbia and Harvard, the whole history of relations between Ukraine and Russia was one of risky (Ukrainian) universalism encountering powerful (Russian) provincialism. His essays, published in Ukrainian in 2013, provide a learned guide to this durable perspective.

In the early eighteenth century, at a time when religion was seen as the essence of culture, Ukrainian churchmen believed that they were bringing universal Christianity to the Russian Empire. From the perspective of Kiev, Christianity was a faith that had been tried by multiple crises, and Orthodox Christianity the proper historical refinement. In Kiev, Orthodoxy was universal in that its thinkers were men of broad culture, and universal in that they expected that their understanding of religion could be extended, for example, to Moscow. The Orthodox Church in Ukraine had a tradition of baroque education in Latin and Polish; its churchmen were aware of all of religious controversies that had riven Europe during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. The Russia of that era had no such institutions, traditions, or contacts. Moscow accepted the churchmen's services but reversed their message: the Orthodox Church would be seen as authentic, not because it represented a transcendental alternative to secular states, but only insofar as it enforced Russian political power. It is no accident that the Russian Orthodox Church today is a strong supporter of Russian militarism.

The next great encounter between universal and provincial values in Ukraine and Russia and their borderlands came with the rise of communism in the early twentieth century. In Kharkiv, Shevelov lived through, and was formed by, an attempt to turn communism into a kind of global project of the enlightenment of nations. When the Soviet Union was established, Ukraine was its second-most important republic (after Russia), and Kharkiv was the first capital of Soviet Ukraine. Inspired by the creation of the Soviet Union as a federation of national republics and supported by early Soviet policies of affirmative action for non-Russian nations, many Ukrainian communists took the international character of the revolution seriously, believing that all nations would now undergo transformations of society and culture as they advanced towards socialism. As they saw matters, Ukraine was one of countless nations that would bring about this revolution by fashioning a modernist art and literature appropriate for the new socialist age.

In the 1920s, under the leadership of the Ukrainian proletarian writer and poet Mykola Khvylovy, Ukrainian communists established an exemplary set of cultural institutions promoting experimental culture. Khvylovy's main idea as a critic and sponsor of new literature was that Ukraine could leap forward to what he called a "psychological Europe" by way of a new Ukrainian high culture that offered fearless meditations on the predicaments of modern life. By "Europe" he meant the embrace of Europe but also the attempt to transcend its genres. He saw this as the appropriate task of Ukrainian and Russian literature, separately, and rejected the idea that Russian culture had forms beyond the European and that these should guide Ukrainian writers. Some of the best novels of the period, such as Valerian Pidmohylny's The City, are about the experience of socialism in Ukraine's great cities. Khvylovy himself described living in Kharkiv in a way that is hard to experience as romantic: "In a faraway church a fire is burning and forms a poem. I am silent. Maria is silent."

But then, as Shevelov saw it, came Joseph Stalin and a new ideology of Russian provincialism. Soviet socialism was no longer a universal project that could begin from nations building a new European culture, but rather a highly centralized economic transformation, directed from Moscow, whose failures could be blamed on the satellite nations, above all Ukraine. The collectivization of agriculture, begun in earnest in 1930, was supposed to transform the agrarian population of places like Ukraine into modern proletarian societies. Deprived of their land and of its fruits by collectivization and requisitions, peasants in Soviet Ukraine starved and sent their children to the cities to beg. The Kharkiv police were expected to remove two thousand hungry children from the streets each day in early 1933. Khvylovy and the other Ukrainian writers saw this with their own eyes.

Stalin blamed the failures of collectivization on Ukrainian nationalism and punished the leaders of the new Ukrainian avant garde. In March 1933 Khvylovy killed himself. In 1934 the capital of Soviet Ukraine was moved to Kiev. In 1937 and 1938 Kharkiv became one of the centers of Stalin's Great Terror. An entire generation of artists and writers (including the novelist Pidmohylnyi) were murdered by the NKVD. After the Soviet Union invaded Poland in 1939, Polish prisoners were transported to Kharkiv to be shot. The idea of communism as international liberation everywhere was replaced by the Stalinist conceit that communism was a specific system of political control directed from Moscow.

From this perspective it is easier to see how many Ukrainians today understand their own most recent revolution in 2013 and 2014. For Ukrainians, the promise of Europe is not only as a common market for Ukrainian goods and a spur to political reform; it also figures as an idea of reciprocal recognition of European states and civil societies that could bring Ukraine out of the shadows of Russian provincialism. But the revolution--though its activists came from throughout the country--was concentrated on the Maidan in Kiev. In the postwar decades, Kiev was the Soviet capital; in the post-Soviet decades, Kiev has become a proudly European metropolis. In the eastern city of Kharkiv, where Sovietization after 1930 meant provincialization, the atmosphere is much more post-colonial. During the revolution, opinions in Kharkiv were very much divided, with a large number of people joining an "Anti-Maidan" against the pro-European movement. This was an encounter between violent and non-violent methods of protest, as the Anti-Maidan specialized in beating and humiliating their political opponents. Serhiy Zhadan, Kharkiv's best-known poet and novelist, had his skull broken by the anti-Europeans in early 2014.

After the victory of the Maidan and the Russian invasion of spring 2014, the tone in Kharkiv changed somewhat. The city's Lenin statue was finally brought down in September 2014. A sign hangs proclaiming that the plinth on which it stood is "under construction," though no actual construction is underway. (The kind of construction that is meant is perhaps of the cultural or political variety.) Kharkiv's leaders generally opposed the Maidan but also, when the time came, opposed separatism and the Russian invasion. On the streets, right-wing paramilitaries recruit for the defense of Ukraine from Russia, even as much popular opinion is uncertain how to think about the war. In February, residents of Kharkiv marched to celebrate the anniversary of the Maidan; someone laid a bomb on their route, killing four people. The city buses are painted blue and yellow, the national colors, with the hopeful message "one country" written in both Ukrainian and Russian. Recent efforts to commemorate Shevelov himself have revealed the divisions. A plaque mounted in Kharkiv to recall his life and work was promptly destroyed by people who claimed that they were defending Kharkiv from "fascism."One of the people who have tried to return the memory of Shevelov to Kharkiv was Zhadan, the poet who was attacked last year. The subject for which he is best known is the experience of post-Soviet life in big cities. In a major prose collection, Hymns of Democratic Youth, published a few years before the Maidan, he portrays the beginnings of the latest Kharkiv, the post-Soviet one. The first story in the collection, "The Owner of the Best Gay Club," is probably not best read as resistance to the official homophobia of the Russian Federation or the anti-gay sentiments that are still dominant in Ukraine. Its message in the end is less about the particularities of the gay experience in Kharkiv or of the tragicomedy of those who seek to make money from it, but rather on the nature of love. In the end we learn that the titular figure, the manager of the best gay club, a former street enforcer, secretly believes that gays must be the ones who understand sex. In the end, even that turns out not to be so simple. The story sublimates the particularities of provincial post-Soviet Kharkiv into a universal question, whether love between two people can be a response to the overwhelming alienation of a society in profound transformation. This is a serious move executed quickly and skillfully against a comic backdrop, leaving the reader wanting more.

Back in 1920s Kharkiv, the communist leader Khvylovy was also writing about the difficulties of passion in the modern city among many other themes that were thought of as part of the new universalist future. It might seem at first, though the conclusion would be too easy, that Zhadan, who was born in 1974, is simply chronicling the long decline of Khvylovy's city and its mission. What Zhadan actually seems to aspire to--and here his willingness to risk his life for Europe is a clue--is what Khvylovy called "psychological Europe": the acceptance of conventions, the work to transcend them, and the absolute indispensability of freedom and dignity for the effort. The thugs broke his skull because he refused to bow down. Zhadan's most recent work, a collection of poetry published earlier this year entitled Lives of Maria, is a book of Ukraine's war and of Zhadan's own survival: "you see, I lived through it, I have two hearts/do something with both of them." Yet as the book proceeds the meditations are increasingly religious, the poems often taking the form of conversations with Maria herself. No one, in eastern Slavic culture or anywhere else, combines the writerly personas of tough guy and holy fool as does Zhadan. He raps hymns.At points in Lives of Maria, Zhadan sounds like Czesław Miłosz, the twentieth-century Polish poet, who also strove toward Europe through both the local and the universal: "I wanted to give everything a name." Miłosz was the preeminent poet of a borderland, one to the north of Kharkiv, Lithuanian-Belarusian-Polish (and Jewish) rather than Ukrainian-Russian (and Jewish). His position, not so different from Zhadan's perhaps, was that Europe can best be recognized on the margins, that uncertainty and risk are more substantial than commonplaces and certainty. And indeed, the last section of Lives of Maria is devoted to Zhadan's translations of Miłosz. Zhadan begins with two of Miłosz's poems, "A Song on the End of the World" and a "A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto," that ask the most direct questions about what Europeans did during the twentieth century and what they might and should do instead. The second poem communicates the pain and difficulty of actually seeing and trying to learn from the Holocaust, which was, or at least once was, a central idea of the European project. The first transmits, almost breezily, certainly eerily, what a European catastrophe might feel like. It concludes: "No one believes that it has already begun/Only a wizened old man who might have been a prophet/But is not a prophet, because he has other things to do/Looks up as he binds his tomatoes and says/There will be no other end of the world. There will be no other end of the world."

Where Miłosz wrote in Polish that the old man had other things to do, Zhadan writes in Ukrainian that there were already so many prophets. Perhaps so. Pro-European Ukrainians are taking a chance, not demanding a future. They watch the Greek crisis too, and their position is often more scathing than anything western critics of the EU could muster. The point then is not certainty but possibility. Zhadan might well have died for an idea of Europe; other Ukrainians already have. Yet the risks he has taken, both physical and literary, are not in the service of any particular politics. Many of his essays and poems are about the attempt to understand people with whom he disagrees. He is an outspoken critic of his own government. Like Miłosz, who described Europe as "familial," or like Khvylovy, who called Europe "psychological," Zhadan is pursuing experimentation and enlightenment, a sense of "Europe" that demands engagement with the unmasterable past rather than the production and consumption of historical myth. "Freedom," writes Zhadan in Lives of Maria, "consists in voluntarily returning to the concentration camp."

No one can know where this vision of Europe might lead; that is, in some sense, the point. But we do know that for Europe to exist as such it must also exist in broader institutions. Many Ukrainians understand this, which is why they made their revolution about Europe itself. These institutions must be improved, which is why we are all talking about Greece. Europe can fail in both Greece and Ukraine, which is why the Russian media in these weeks abounds in prematurely celebratory visions of a collapsed European Union. The underlying message of Russian propaganda is that working for Europe, whether inside the European Union or beyond it, makes no sense, since democracy and freedom are nothing more than the hypocrisy of a doomed order, and history has no lessons other than those of power. Russian nihilism cheers on European narcissism.

The European Union will no doubt survive both crises, at least for a time, but in neither has it provided much of a response to its existential and democratic problems. Ukraine deserves help but is largely ignored because it is not a member of the European Union; the Greek prompt for institutional reform is going unheeded. As European leaders struggle to define what Europe is, it is more useful, or at least more heartening, to read the grim universalists in Kharkiv than to watch the gleeful provincials in Moscow.

August 23, 2015

Painting is a Globe

A ruler is a straight line, level like a horizon, divided into regular segments. Distinctions are drawn and sides chosen for the fight. Differences are delineated. In representation, things are figured out. Abstraction, on the other hand, tends toward the field, the all-over, the monochrome, the elimination of distinctions that characterize representation and figuration. Abstraction is erasure. Remember that Rauschenberg erased De Kooning, bringing about the postmodern eclipse of the modern and the dawn of the ultimate erasure of the conceptual.

Both poles of abstraction and representation are arrested by stasis. Each is a kind of death: the former by dissolution and the latter by fixation. The abyss and the frozen sign. Disintegration and rigor mortis. Somewhere strung between these extremes is the flux of the interpolated center, where equilibrium rapidly exchanges from one pole to the other in very, very small alternations, like the ghostly transactions of some high orbiting electron cloud.

Take this tensed line and position it into a vertical axis. Spin the line, it will arc and become longitudinal. A centrifugal force compels the stations along its length to become latitudes. We have before us, a sphere. Slewing latitudes could be an expression of flux, infinite as a circle, the scope of freedom of action or thought. Thus, a line becomes a globe and another way to see painting.

Let's call the north pole, figuration and the south pole, abstraction. Life is difficult unto impossible at the poles. Nothing grows there. One's very clothes become the last redoubt as a life support system. The closer one gets to either extent, the stranger the weather gets. What seemed simple, direct and straightforward before the journey becomes anything but straightforward at its crest. Should the flag be planted in the magnetic or geographic or political pole? There are no landmarks to establish a location. Blizzards obscure position. The goggles are iced over. Supply lines are strained and broken. The freezing temperatures have blackened fingers and toes. Life retreats to the core of the body. At the end of the day, (a fashionable phrase these days that piques my interest), does this kind of exactitude at the poles really matter? Who among us can reasonably argue that we must plant yet another flag on either pole? Like the pointless reconquest of Everest, so littered with trash, spent oxygen bottles and vainglorious corpses, hasn't the existence of the poles already been very well established by now?

The globe of painting becomes interpolated in coordinates of latitude and longitude. The painter's world becomes unfolding horizons of mountains and seas, zones of weather tropical and temperate, bays, inlets, rivers, deserts, canyons, archipelagos, ridges and peaks both abyssal and mountainous. Tropics of Capricorns and Cancer, equators and datelines mark the sphere.

Yet horizons bend and questions remain. An insertion between two known points is an interpolation. In mathematics, interpolation is a calculation, the result is fractional with a numerator and denominator, which can either be rational (finite) or irrational (infinite). What does it mean to arrive at an irrational interpolation between the poles of abstraction and representation? And finally, what does it mean that this axis between the poles of abstraction and representation require a spin and a centrifugal force to generate the planetary form of painting suggested in this essay? What causes this spin? Is the volumetric nature of paint itself, centrifugal? Does the spin rotate perfectly, or are there perturbations of significance such as precession? Would life exist on earth or in painting without such perturbations? And what exactly is the force at right angles to this axis?

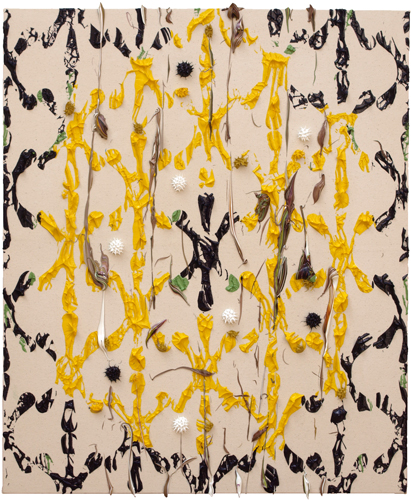

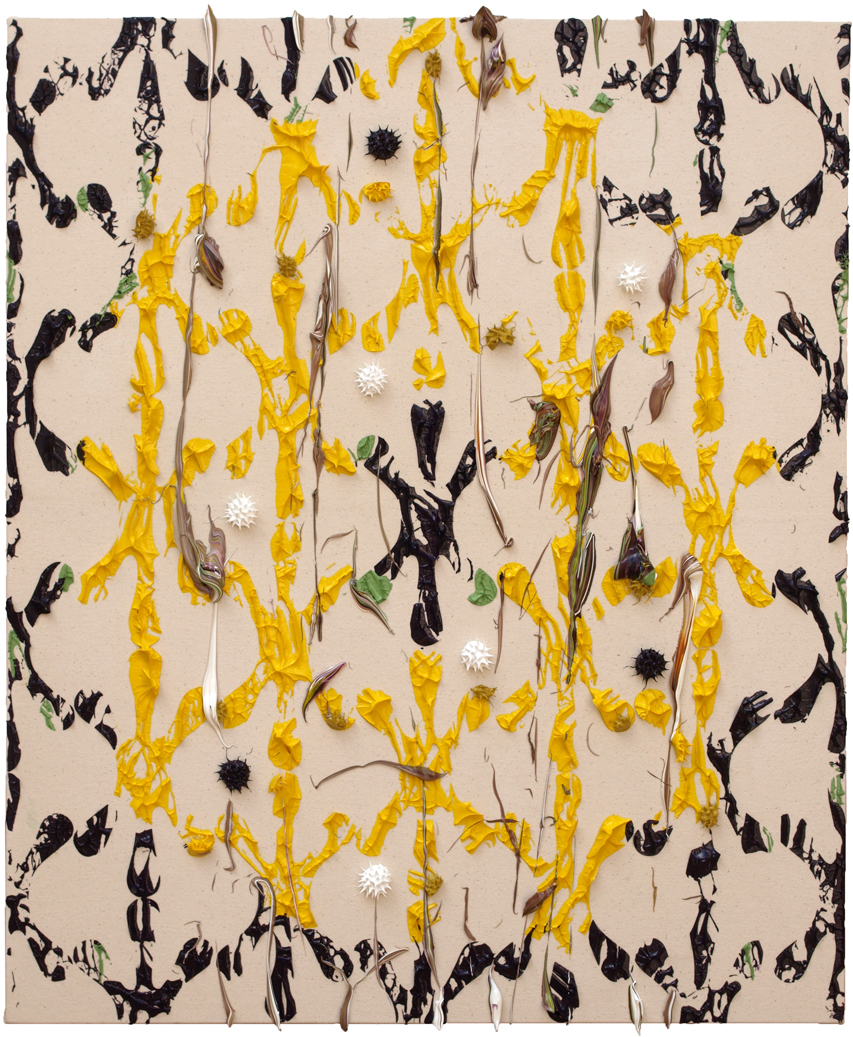

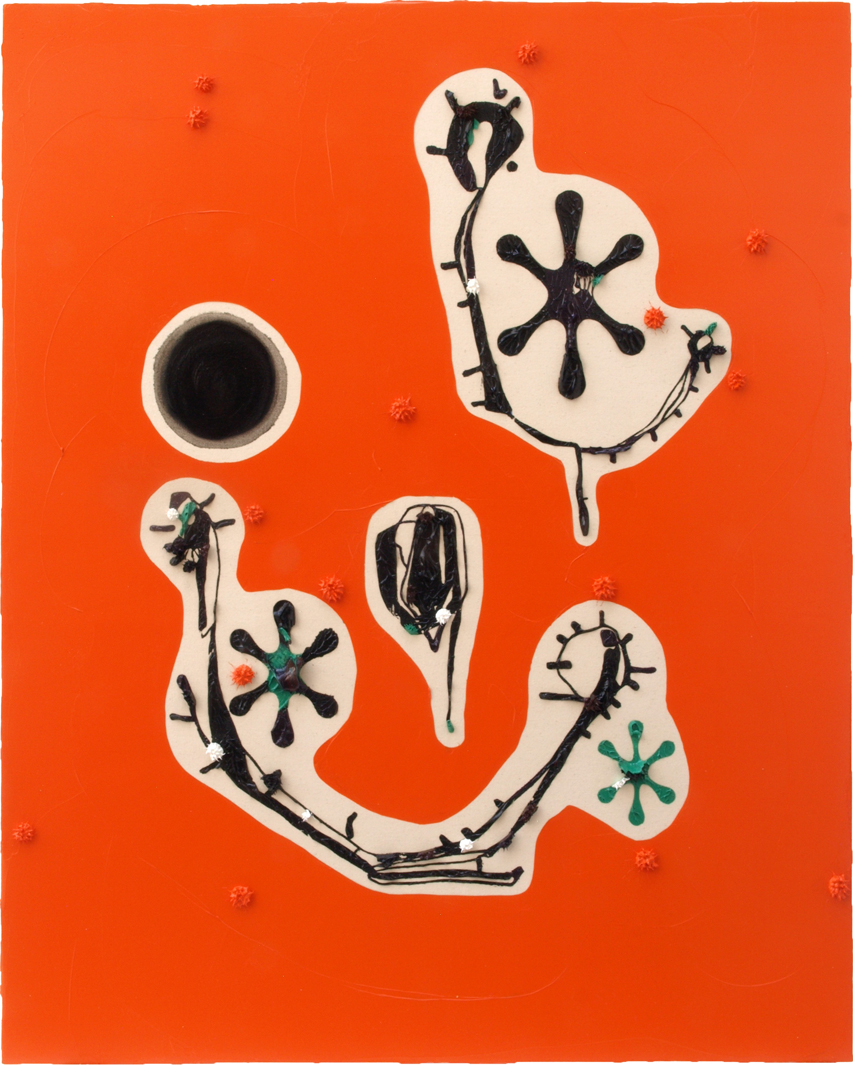

rauxa y seny

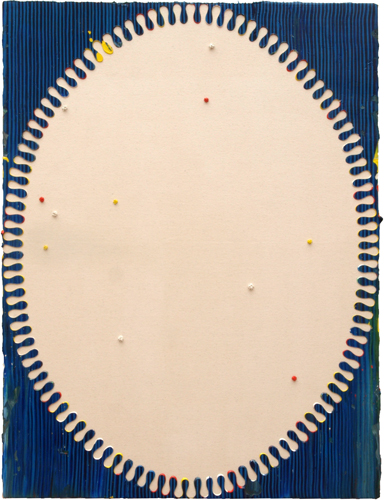

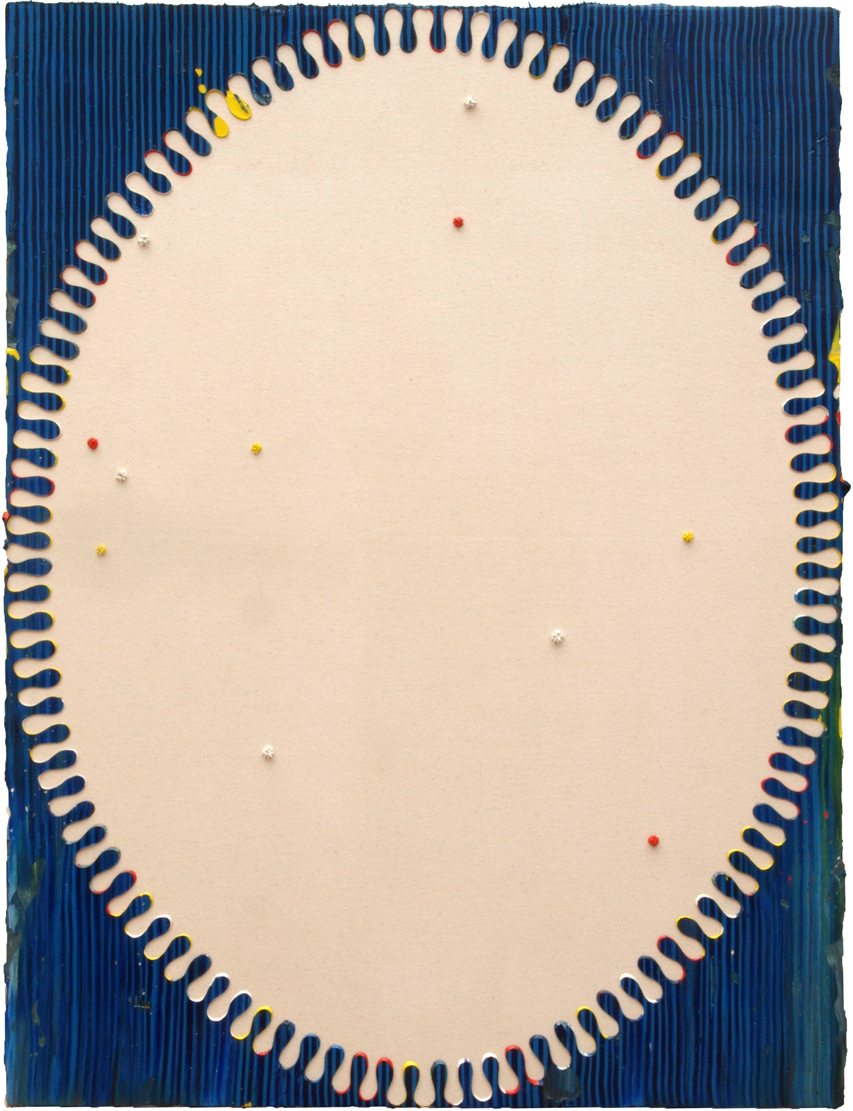

rauxa y seny

2015

#504

150x120cm

Oil on Canvas

August 21, 2015

a enemigo, ni agua

a enemigo, ni agua

2015

#503

150x120cm

Oil on Canvas

August 13, 2015

the reassuring littoral

the reassuring littoral

2015

#502

150x120cm

Oil on Canvas

August 9, 2015

Ajo y Agua

2. Ajo y Agua

My Filipino grandfather, Pacifico Garcia, known to us in the family as Papang, would say: "Lean like a tree in the direction that you would like to fall." Later in life, I learned that this was a typical Spanish expression. Spanish is more limited in vocabulary than english and as a result, the language must be used much more poetically. This apparently accounts for the rich abundance of proverbs found in Spain.

Papang sent his nine children to Madrid in the later 1950's to finish their studies, thus conferring the higher status of a Spanish education in post-colonial Philippines as a potential advantage to his offspring. My father was an air crash rescue firefighter in the Air Force at that time. Shortly before that, he was a soldier and survivor of the Pusan Perimeter in the Korean War. He was stationed in Torrejon airbase near Madrid at the time when the dictator Franco first opened Spain to the post WWII world. In Madrid I was born, and even though we left Spain when I was three years old, I had always held Europe and especially Spain as reference point in my life.

Growing up, I leaned like a tree towards the direction of a life that combined Spain and the USA. In the past fifteen years, my wife and I have fallen in that direction when we managed to buy a house in a small village north of Barcelona called Tossa de Mar. It's a long story but suffice it to say that even though many in my Filipino family had immigrated to Australia, over the years they would tend to flock in vacation to this little fishing village in the base of the Catalan Costa Brava, my mother following them and finally, my wife and I too. While the dream is to live six months on one side of the Atlantic and six on the other, in the meantime we do what we can given the opportunities our careers have afforded us. Mostly, we spend the summers there where I paint as much as I can so that my galleries in Europe can have access to my paintings without too much of an expense in shipping. I can't say that this dream has been fully realized, it's a struggle yet to establish this life on firm ground. We still are leaning and still have yet some distance to fall in this direction.

One of the profound delights of living in Spain are the people themselves, so rich in character, deep in history, delightful in culture and expression. They're a bottomless well of inspiration. One such character is my carpenter, Ramon Gascon. Usually back stateside, I build my own panels over which I stretch canvas for my paintings. But in Spain with time at such a premium, I contract this task out to Ramon. In Tossa, Ramon keeps what I call "office hours" (the early evening after work) at one of the local bars, where time, wine, beer and tapas abound. By the end of the 20th century, the main economy of Tossa shifted from fishing to tourism and as a result most of the locals are multilingual. Some are merely competent and some are connoisseurs. Ramon is a man who savors language and a conversation with him usually has one of two modes: either a dissection of etymological roots or savoring song lyrics (he's also a musician) where he likes to luxuriate in this kind of popular poetry.

This summer happens to be a particularly hot one. Week after week has staggered in stifling humidity. As we sat at the cafe during Ramon's office hour, his greeting to a passing local asking how things were going for him resulted in the shrug: "aguantarse". This means roughly, "I'm hanging in there." At that moment, Ramon seized upon the opportunity to broaden my understanding of Spanish. With a gleam in his eye, he looked to me and said theatrically: "Ajo y agua." As he was eager to do, he explained its significance.

Ajo y agua is a condensate of "a joderse y aguantarse." Ramon spent several minutes unpacking its meaning for me. Ajo is garlic and agua is water. One folk cure is to chew some garlic and wash it down with a glass of water. Where a mild medication is suggested, a stronger remedy is sure to follow. A transliteration of ajo y agua results in "go screw and control (or sustain) yourself", or sharper: "fuck and keep your shit together". A better translation is that it means that "one should just put up with it (hard times) as best as one can." Of historical note, this phrase is supposed to have been coined in the dictatorial years of Franco, and its meaning referred to keeping your mouth shut and out of trouble with the thought police. Now it means a shrug of the shoulders, that you are coping well enough.

Joder as an expression is straightforward and direct. We in the States use the pejorative fuck in the same way spaniards use joder. There are many ways to fuck but fucking is really one kind of act, very, very specific, hard to confuse with any other. Singular. Aguantar is much more evasive, subtle and flexible. Aguantar can mean support or sustain or maintain or abide or endure or suffer or weather or brook or stick out or stomach or hold on or hold out or wear or sit down under or ride out or hang out. The two opposing ideas, joder and aguantar, in meaning and suppleness are welded in composite, the distance in their meaning bound in tension.

Robert Hughes wrote about another, nearly identical pair of ideas in the opening pages of his 1992 book, "Barcelona" (p.24, highly recommended). About the character of the Catalans, he singled out the mirrored ideas of rauxa and seny. Rauxa is outburst, chaos, eruption, a sudden release of strong emotion. Seny is sanity, common sense, judgement, level headedness, shrewdness, wisdom, resourcefulness, street smarts, enterprise. A pair, a set of ideas in tension. Dionysis and Apollo, weren't the ancient Greeks also adept at embracing the complementariness of human character? Human beings, in their vision, were tensed between poles. Life was strung between destinies.

Keeping distinctions distinct is one habit of mind. Combining distinctions is another. Distinctions are usually drawn, with a pulling action such as a pencil lead dragged onto the surface of paper or a window blind pulled down. Delineation. Drawn-to. Representation. Erasure might be considered a pushing action as boundaries are blurred and deconstructed. Walls that separate are torn down. Distances are leaped, signs removed. Drawn-away. Abstraction. The act of drawing, of representation, of picturing might be compared to seny, civilizational in a constructive, analytical sense. Erasure by contrast is barbaric, destructive, interpenetrating, fecund... and notably also: remote, conceptual, ideational, abstract. Ajo y agua, a joderse y aguantarse, fucking and keeping one's shit together, the Mediterranean character of rauxa and seny, abstraction and representation: each side is a sharpened and very useful distinction. Each set is also simultaneously, two sides of the same coin.

friendly, unknown or hostile

friendly, unknown or hostile

2015

#501

150x120cm

Oil on Canvas

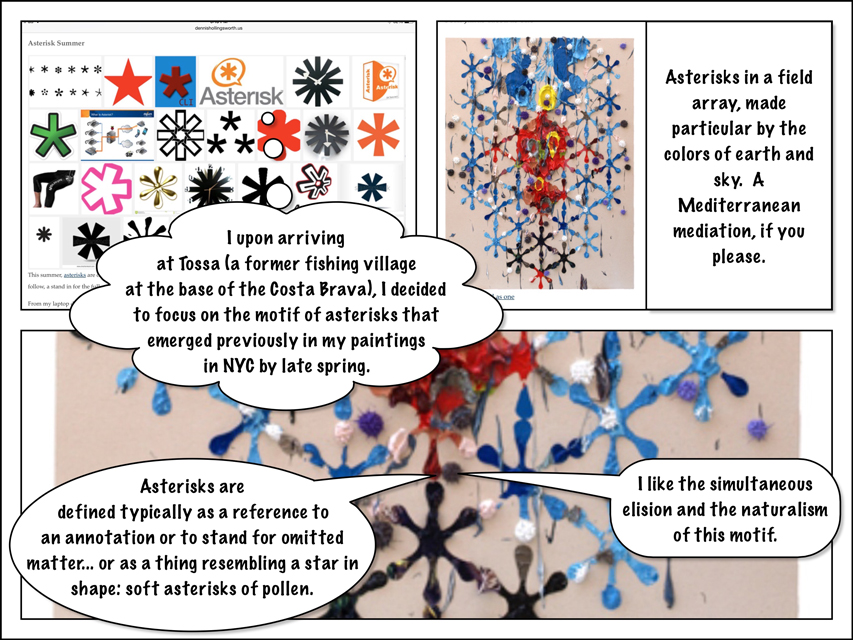

Asterisk Summer

This summer, asterisks are on the brain. I resist explaining why this is so... although I could go on and on about it. Let this blogpost be a reference to an annotation to follow, a stand in for the full aria soon to come.

asterisk |ˈastəˌrisk|

noun

a symbol (*) used to mark printed or written text, typically as a reference to an annotation or to stand for omitted matter.

• a thing resembling a star in shape: soft asterisks of pollen.

verb [ with obj. ] (usu. as adj. asterisked)

mark (printed or written text) with an asterisk: asterisked entries.

ORIGIN late Middle English: via late Latin from Greek asteriskos 'small star,' diminutive of astēr .

August 8, 2015

Negating Negation, Embracing "Negation"

Episode 120: A History of "Will" with Guest Eva Brann (Part One)

The philosophy podcast The Partially Examined Life is absolutely wonderful. This episode had me riveted.

We discuss Un-Willing: An Inquiry into the Rise of Will's Power and an Attempt to Undo It (2014) with the author, covering Socrates, Augustine, Aquinas, Heidegger, Nietzsche, Sartre, compatibilism, the neurologists' critque of free will, and more.What is the will? Is it an obvious thing that we all can see in ourselves when introspecting? If so, then why is there so much disagreement in the literature about what it is? (e.g., Is it a causal force or just an epiphenomenon? Is it opposed to desire or the expression of desire? Is it an expression of individuality or is it a trans-personal force à la Schopenhauer?)

Eva (whom you may recall from our Heraclitus episode) thinks that the notion is a historical artificat that causes needless philosophical confusion, and worse, has had a damaging effect on our culture.

T= 38 minutesPEL: When you say that Augustine introduces the notion of the will to the West, it is the notion of the ability to resist good, the good being God and subsidiary goods being self creation and the ability to say no to the commands of God and to resist the beings that are good in the world. That's the primary new characteristic that's embodied in this new notion that he calls voluntas. When you talk about Confessions, you bring up the famous scene of the pears, maybe you can recount that section ?

E.B.: He and a bunch of boys of about 14 years old adolescents went into somebody else's garden that had a pear tree that had nasty, bitter, unpleasant fruit and collected sacks of them. The point that was -at least for Augustine, I don't know if the other boys thought this, it was a lark- the point is that for Augustine , it means that he engaged in evil-doing, for the sake of transgression. He didn't want the fruit of this evil doing as something he wanted, he wanted, he did it in order to be bad.

PEL: You quote him as saying: "I loved my own fault".

E.B.: And this is what sinfulness is, not doing wrong but loving it.

PEL: And in that way, it's the birth of the will. This is the most clear sign of willfulness, of doing something sinful for its own sake.

T= 43 minutes

E.B.: When you think about the Old Testament, something becomes explicit about that when you think about that notion of sinfulness. That is to say of the person of the will, of a desire to do bad, of the sense of doing evil, for that to come about, you need the notion of the God who made you, of a creator God to rebel against. [...] The matter of issue here is that sin, evil, becomes desirable . In other words, Augustine's will is the will that makes sin desirable as being self assertion against the creator. It's a form of rebellion.

PEL: It's about independence [...] and there's something about Augustine's formulation that you want to undo.

E.B.: The reason why its a serious matter [...] it''s so closely connected to the notion of freedom and independence. It raises the question whether freedom and independence aren't some way allied to perversity.

I'm transcribing this bit from the PEL podcast, thinking about Recent Preoccpations, a blogpost focusing on Miro's statement that he wanted to murder painting, taking on face value from Briony Fer's book "On Abstract Art", that Miro came to this position from his association with Bataille and his Acephale group, which I understand as an effort to process the disruptive influence of collage on the development of modern art. I relished the fact that they walked the hazardous line between poetic interpretation and pig headed literalness in fetishizing dismemberment to the point of coming to the brink of selecting one of their group as the subject of a ritual beheading. The fact that they ultimately balked has a meaning more significant than the salvation of their souls or their humanity, I think that this is a salvation of their intellect in that they recovered the distinction between imagination and reality.

I transfer this theme to the general argument about transgression in painting, from my days in grad school where I balked at the presiding proscription against painting, the then already long running meme about the death of painting (it still persists today in most sectors of the art world despite the bloom of painting after the 90's). The Miro quote forces me to confront the depth of this meme in art history and ultimately I am trying to convey an argument to my peers that the recurring meme about the death of painting requires the provisional quotational frame. Instead of the death of painting, we should instead substitute the "death of painting", and therefore balk, like the Acephale group, at crossing the line from poetic flight into pigheaded literalness.

To the point delivered by Eva Brann above: Bataille was a seminary student prior to his conversion to (transgressive) art. Augustine was a saint of course and according to Brann, the primary philosopher of the will. Relish the contradictions of negation. Negation at the higher altitudes seems to require a certain kind of intense religiosity... faith. Could the murder... "murder" of painting require a certain, specific kind of qualified actor? A high priest of painting?

I feel compelled to add a reference to Paul Berman and his 2004 book, Terror and Liberalism, where his argument could be summarized as an effort to draw the line between liberty and libertinism. My summary of his opening argument lies below the fold:

Paul Berman, Terror and Liberalism:

He's looking for the roots of totalitarianism in Western Civilization, of how Liberalism sprouted self hate, a death wish, of how this death wish corresponds and even coordinates with radical Islam

In the first hour of the book, he follows the following chain of reasoning, he traces the historical evolution of Liberalism's death wish:

From

Tariq Ramadan http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tariq_Ramadan

-his starting point, he is asserting that what is happening in the MidEast is connected to the West

-Ramadan wrote about Camus, both are North Africans

-Berman does not say but I remember as I listen that Radical Islam loves death more than we love life

to

Camus, "The Rebel"

to

Victor Hugo, "Hernani"

-murder as an act of rebellion which ends in suicide

-a romantic expression

-aimed at freedom but ended with murder and suicide

to

Baudelaire, "Flowers of Evil"

-rebellion in the name of the absolute freedom

-murder and suicide for its own sake

-crime as poetry

(Sade is in the chain too)

to Dostoyevsky, "The Brothers Karamazov"

-the character of Ivan: "Everything is permitted"

-a world where values do not exist and everything is permitted

to

Andre Breton's Surrealism

-"The simplest of Surrealist acts consists of going down to the street,

revolver in hand and shooting randomly into the crowd"

-the theory of the gratuitous act is the culmination of the demand for absolute liberty

The culprit: Absolute Liberty.

From Berman:

...and now the deepest disaster of all got underway. The old romantic literary fashion for murder and suicide, then the dandy's fondness for the irrational and irresponsible, the little nihilist groups of Left Wing desperados with their dreams of poetic death, those several tendencies and impulses of of the 19th century came together with a few additional tendencies that Camus never bothered to discuss, the dark philosophies of the extreme right in Germany and other countries with their violent loathing of progress and Liberalism, the anti-semites of Vienna with their mad proposal to cleanse Vienna of their most brilliant aspects, the demented scientists of racial theory, all this which once was small and marginal began to metastasize and spread the cult of death and irrationality began to take hold of entire mass movements. The mass movements began to transform into something new and entirely different...of a new type... a hatred of liberal civilization...

***

This all goes to transgression and how we take it for granted, of how we underestimate how it is explosive/toxic to civilization. Transgression is like a substance like lead or radium or mercury which was treated initially in a cavalier manner, and only after disaster did people take the precautionary steps to treat it with the requisite safety procedures to conserve and protect life. I'm saying that the celebration and exploration of transgression in art should have similar prophylactic measures associated with it, intellectually. Otherwise, we, in our creative Liberal world will become unwitting collaborators in its (our) own destruction.