May 16, 2017

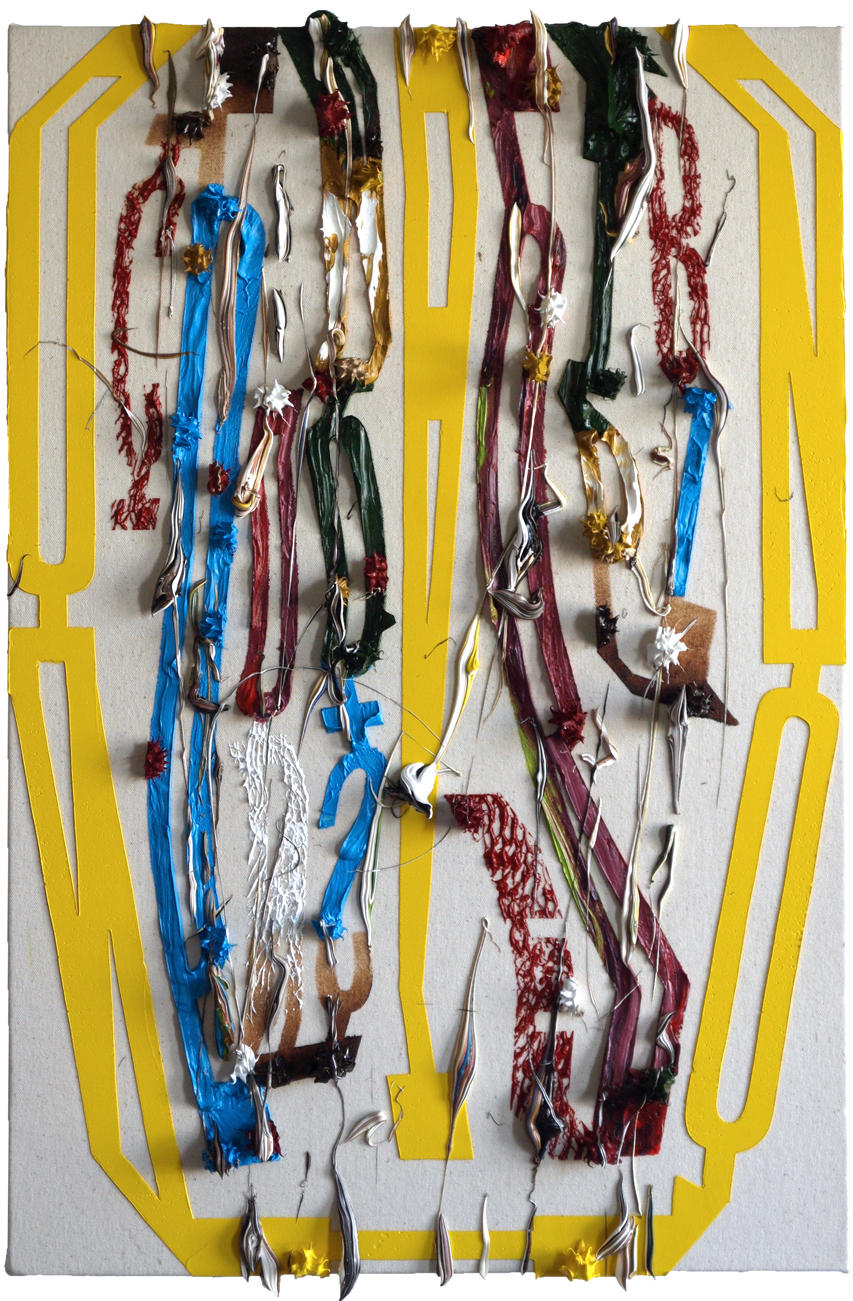

strange that we could be intoxicated

strange that we could be intoxicated

2017

#543

30"x20"

Oil on Canvas

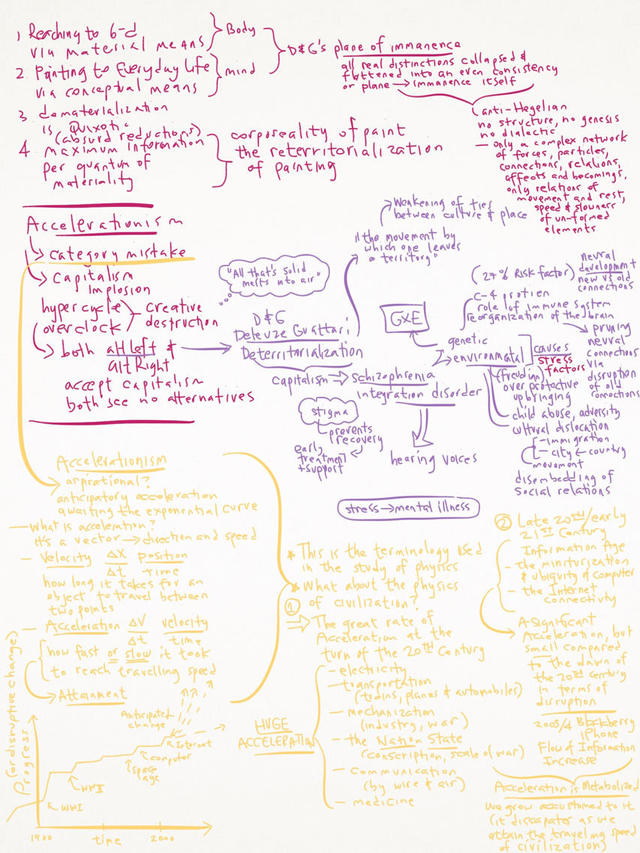

Considering Accelerationism

A friend sent me a couple of articles about chatter concerning a revival of a movement called Accelerationism.

Accelerationist Art by Rob Meyers

The Dark Enlightenment by Nick Land

My friend's over-riding concern is about the changing nature of the art world and his anticipation of or adaption to the avant gardist horizon. His diagnosis is that recent events have decimated the business of the art world: speculative practice has destroyed lower and middle market and shifted activity exclusively towards the high end, younger artists and galleries have capitulated to zombie formalism to cater to the market shift, that all existing categories of art making are antiquated beyond redemption. His prescription for artists is to seek patrons in big business, create projects directed towards the market at large and generally be an asset geared to the operations of the emerging global economy. He says that the old model is dead and will not revive, collectors as we knew them no longer exist.

Naturally, the painter in me chafes at these suggestions, but there is little to refute of his diagnosis despite my resistance to his prescription. All I have in response is the hope that all of this is a lull and merely a moment in a cycle soon to revive. My shield of faith in the eternal vitality of painting trembles in the face of his critique. I yet take his argument seriously and I study his evidence intently.

Rob Meyers introduces Accelerationism thusly:Despite its image of rapid technological change, progress under capitalism has stalled. Spinning ever faster is not the same as going somewhere. Contemporary Accelerationism wants to take off the brakes, and it is enlisting art's help to do so. [...] Accelerationism [...] is an attitude of "prometheanism", of amplifying our capabilities, of rationally overcoming intellectual and material limits. Of hacking the systems of philosophical and political thought to find the exploits that will allow us to increase our knowledge of them, our control of them, our reach through them. Hopefully this will work out better than it did for the original Prometheus of Greek myth...And Andy Beckett treats his definition in the Guardian's Long Read, Accelerationism, How a Fringe Philosophy predicted the future we live in:

Accelerationists argue that technology, particularly computer technology, and capitalism, particularly the most aggressive, global variety, should be massively sped up and intensified - either because this is the best way forward for humanity, or because there is no alternative.

Accelerationists see that the cure for the cupidity of capitalism is to overclock creative destruction. It's particularly notable that this movement (if it can be called one at this early stage) possesses adherents from both sides of the political aisle, AltLeft and AltRight. Both accept capitalism at face value and both see no alternative to it. Bipartisan support for an art movement --much less the appearance of a Rightward aesthetic-- this is as rare as a unicorn.

I noted with interest in my readings, compelling references to Deleuze & Guattari's deterritorialization induced by change wrought by capitalism. Schizophrenia in this testimony is an integration disorder generated by the sweeping operations of modernity. As I drill down into this illness proper, I note that the human mind requires periodic neural reorganization. Even the brain requires creative destruction! What scientists know so far, is that the brain must prune neural connections -to have the capacity to forget, in other words- so that we can learn anew. Of particular note is the role of the immune system in this process, the exact nature of which we are only now beginning to understand. D&G present an attractive case for exploring the dynamic of schizophrenia for creative exploit. We are the children of the umbrella on the operating table, after all.

Deterritorialization and reterritorialization is another way to say creative destruction. The alienation and stress that arises when "all that's solid melts into air" is a stressor specific to modernity. Recent generations had vague concerns that their careers remained viable by the time that they retire, current generations are wary that their chosen occupations could become obsolete at the snap of a finger and that there is a high probability that retraining into new career paths could happen at least once if not multiple times in a working life... a working life, meaning, a whole lifetime since retirement itself is quickly becoming an antiquated idea. Deterritorialization and reterritorialization is also a way to describe the stressors of shifting cultures in an age of jet travel, immigration and information -internet- flows. Learning and adapting to one's own culture is enough of a problem, shifting the conditions and adding multiple other cultures to the mix brings any human being to the limits of coping and endurance.

Now, I don't mean to be a contrarian, but to be merely critical in the most sympathetic manner possible. I feel compelled to ask: what if Accelerationism is, for our historical moment, aspirational?

Acceleration is a concept borrowed from physics. Together with velocity, it is a vector indicating direction and speed. Velocity is the change of position divided by the change in time, ∆ x/∆ t, how long it takes for an object to travel between two points. Acceleration is the change of velocity divided by the change in time, ∆v/∆t, how fast or how slow it takes to reach traveling speed.

In other words, acceleration is about attainment.

Acceleration differs by degree of change and direction. A negative example of the latter would be the atavism of ISIS. Acceleration is not the same at different points in history. In terms of the physics of civilization, the change that exploded at the dawn of the 20th century was gargantuan. We have to exert ourselves to imagine what it was like to live at a time when a host of innovations erupted on the scene: the invention of electric light; the emergence of new transportation in the form of trains, planes and automobiles; the mechanization of industry and war; the invention of the nation state and the capacity to conscript entire populations to exploit total war; new communication by wire and air; life extending discoveries in medicine. Yes, the acceleration we have lived through in our emerging Information Age is a marvel to behold. But please allow a possible heresy of suggesting that it was minor compared to the early 20th century. The miniaturization and ubiquity of computers together with the interconnectivity of the internet sped the flow of information to a dizzying degree, but this accelerational change pales in comparison to what happened in the events surrounding WWI. The disruptions wrought by the former is small bore and more gradated than the latter ever was.

The only way to imagine an analog to the acceleration of the dawn of the 20th century is to conjure thoughts of the impact of something truly game changing in civilizational terms. Something like a revolution in energy sources, for example. What if cold fusion wasn't a pipe dream? What if we found an energy source that could eclipse what petroleum can do? What if we could reorganize matter at the the atomic level at will, or transport organic matter over distances, travel in warp drive, such as was imagined in Star Trek? What if we could cure cancer and reverse and control aging? What if robots could build robots? What if we could finally weave carbon nanotubes into cables strong enough to fashion a space elevator? (Lowering the cost of space travel could enable unlimited solar power someday.) What if we actually made contact with sentient alien life? What if utility fog was real? Any one of these wish list items could do the trick of changing civilization into another creature altogether, just as it did in WWI.

This is not to discount the apprehension of the advent of civilizational change, we are chipping away furiously at this wish list and progress is being made. This list could pale at what might actually be just around the corner in terms of change. We don't really know how long we will linger at this brink. It could take another century or two to bring some of it to pass. We might well be waiting pathetically like Godot for the exponential curve to make n approach zero. While we now are on the brink, we are also merely at the brink. This threshold moment might last a very long time or it could collapse fell swoop in the coming decade. Or next year.

We. Don't. Know.

What we do know is that not all acceleration is the same. We know that we have yet to experience change at the scale that it was in the early 20th century. We also know that accelerational change is metabolized, reterritorialized --in D&G's terminology-- with difficulty to be sure and with dire collateral damage, but in civilizational terms, relatively quickly. We grow accustomed to it. Acceleration dissipates as we attain the traveling speed of civilization. It doesn't last long.

What is the impact of all this for the adherents of Accelerationism? I have looked and will look intently at the art offered as examples of it. I have yet to see anything fundamentally different in kind from the art forms arrayed since I was in grad school in the late 80's and early 90's. There are also special problems inherent in the anticipatory nature of an Accelerationist movement: one must necessarily await ones' cue. There is only coping, but not leadership, save the crap shoot of the visionary.

And all the while, there is a siren song of art emulating life and the inevitable absorption of the former by the latter as a result. Art requires the special boundary frame in order to survive contact with life. Life trumps art every time, it will remain much more interesting mano-a-mano.

What remains of all this is the cautionary tale. Beware of wishful thinking. Take out the birthday party decorations only on the day of the birthday. The toughest critique is the glancing comparison to the Futurism of ye olde days. Banish any doubts of this with a quick read of Marinetti's Manifesto. The lesson from this is to have the bridle of enthusiasm firmly in hand, and to be wary of over-inflating prejudices from an earlier soon-to-be-defunct-epoch into the next overcoming one.

***

Postscript:

There is a possibility of a soft acceleration. Instead of the zero to sixty in a couple of seconds g-force slam of acceleration, consider a quarter g-force buckle-your-seatbelt surge of a civilization moving gently past the 500mph cruising speed. No hype, just calm expectation. Maybe this should instead be called Velocityism?

What would that kind of art look like?

May 10, 2017

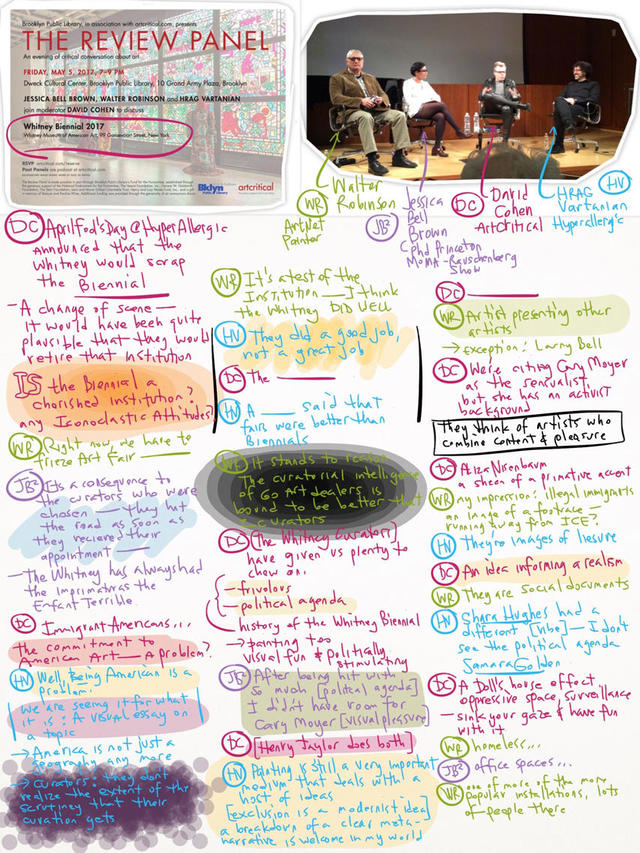

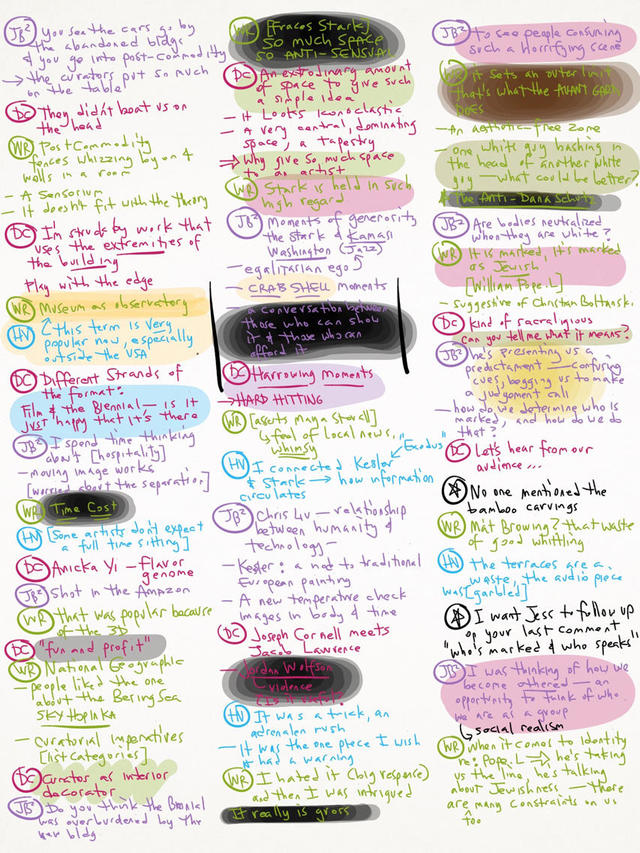

Review Panel: The Whitney Biennale

Last Friday, artcritical's Review Panel met to discuss the Whitney Biennale 2017. The conversation was structured into two parts, the first on the Biennale as a whole, an the second on the recent controversy about Dana Schutz's painting of Emmitt Till.

I took notes.

The most interesting idea discussed that night was that the average art fair is better curated than the average biennale. Brute force curation, sheer processing power is certainly a seductive thought. One exception to this would be that a complex institutional exhibition coheres the curatorial agenda. And the exception to that exception is that an art fair coheres to the agenda of an art fair: sales and the power to attract high value collectors. It's sadly an uncontroversial fact that art fairs strongly influence their customers -galleries- as to what can and cannot be shown. This was one of the driving factors to the recent rise and fall of Zombie Art.

But the abiding critique of the Biennale remains, it's razor sharp. What had happened such that our high level cultural, intellectual institutions routinely deliver a diminished product?

As for the controversy about Dana Schutz's painting, elements of both the panel and the audience hazarded the criticism that Schutz's painting was underwhelming as a painting. The overbearing issues about identity appropriation are incapable of finding a resolution, artistic freedom and racial/cultural respect of identity are today's meeting of the immoveable force and the unstoppable object. My opinion? This paradox points to the quality of Schutz's practice. Schutz is an accomplished and acclaimed painter, no one contests this. She came out of the art school chute blazing and dazzling the art world with paintings that seemed to use the power of literature. Her paintings were radiant with dimensions of short stories or novels. That she did this simply using figuration, composition and titles was a wonder to behold.

Over the years, multiple dimensions fell away into a generalized idea about anxiety or human strife. The complex became simplistic and the faint echoes of cubistic fractured planes can't save the day. (BTW, I sense a harmonic oscillation with the discussion about curation above.) Her theme apparently can find any subject as a home: the claustrophobia of an elevator, inchoate shame, or Black pain. Stepping light footed across a lily pad of subjects went wrong when she found that she lacked sufficient gravitas to tread in the radioactive territory of the Emmitt Till story. There are only two alternatives open to her, a tough place to be for an artist. Artists generally are tasked to fight out of tough places. Either she can do nothing and grant her critics her scalp, or she can paint her way out of the controversy.

Yes, I am suggesting that she paint Emmitt Till again and again for a significant cycle of 20 - 50 paintings, get in there deep and discover something about the subject and herself along the way.

But who am I to say this?

A bird tweeting in the tree.

A taker of notes.

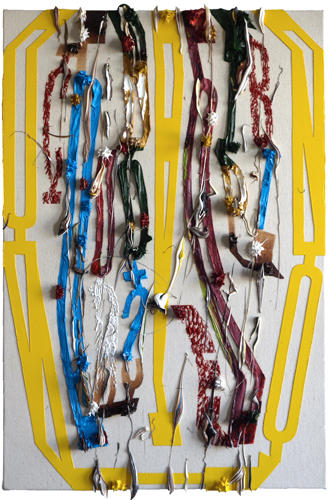

May 8, 2017

Paintings 2016

This is a presentation of paintings from 2016. Sizes of the following images are relative.

Click on the image for enlarged images in the original blogpost of each painting.

pluck the fruit

2016

#514

60"x48"

Oil on Canvas

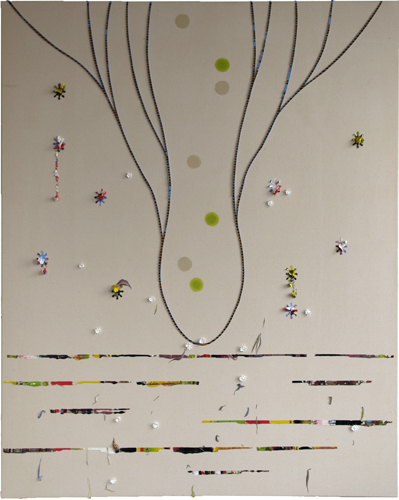

lines between pools

2016

#515

28"x22"

oil on wood armature and canvas

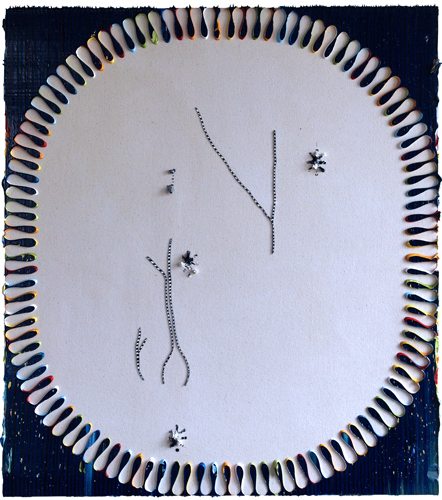

Wellsprings 2016

#516

36"x32"

Oil on Canvas over Wood Panel

Remainder of a Remainder

2016

#517

14"x11"

Oil on tape on Canvas

la abundancia

2016

#518

36"x32"

Oil on Canvas over Wood Panel

vislumbres

2016

#519

36"x32"

Oil on Canvas over Wood Panel

past the end

2016

#520

36"x32"

Oil on Canvas

a familiar desire

2016

#521

18"x12"

Oil on Canvas

psychological basket

2016

#522

18"x12"

Oil on canvas

(Yeah, but what if?)

2016

#523

18"x12"

Oil on Canvas

limelight

2016

#524

18"x12"

Oil on Paper

inception

2016

#525

18"x12"

Oil on Paper

sitting on our haunches

2016

WOP 1-16

46x38cm

Oil on Paper

sitting on our haunches

2016

WOP 1-16

46x38cm

Oil on Paper

an ultimate act of humility

2016

WOP 3-16

46x38cm

Oil on Paper

XOXA

2016

#526

120x90cm

Oil on Canvas

Cáscara de Nuez

2016

#527

80x73.5cm

Cáscara de Nuez

2016

#527

80x73.5cm

La presa

2016

#529

170x153cm

Años de Gloria

2016

#530

120x90cm

quinto piño

2016

#531

81x122cm

explicit or implicit

2016

#532

Oil on Canvas

18"x12"

tincture of artifice

2016

#533

Oil on Canvas

18"x 12"

not merely retinal

2016

#534

18"x12"

Oil on Canvas

Knowing my strength

2016

#535

72"x72"

Oil on canvas

Tears and Tears

When the tears came, I dried them.

When I couldn't, I tore them off.

There were times when I wouldn't tear the tears.

Instead,

I caught them in little cups like fat from jamón.

Shortly before I moved to NYC from LA in 2012, I learned that some of my paintings had begun to weep tears of linseed oil. Naturally, this news was tough to bear. Nearly 16 years of painting were in jeopardy. After the initial panic, I girded my loins. I began to address each malfunction as they arose. Over all these years, I have learned that the malfunction is isolated to a titanium white manufactured by Daler Rowney Georgian. The failure is not uniform, not all applications of this pigment have gone wrong.

I have written emails to the manufacturer with no reply. I can only reckon that the problem stems from additives or fillers such as calcium carbonate that ultimately fail to bond in a matrix of linseed oil that did not oxidize properly in that context. If the problem was an improperly processed linseed oil, then I would see the problem arise in other colors, which has not happened. This fact is one that must be emphasized: the problem is not uniform, only a fraction of the malfunction has presented itself, the percentage of which I can only guess to be 30% of paintings that use white in a mass, a yet smaller subset of the whole. I'm relieved to report that in fact, all other colors dry hard and durably. I have seen the development of the problem in titanium white with first a slow tumescence of oil glistening on the surface of paint (the pigment and filler separating from the matrix of oil) and after several years -perhaps five or so- the oil begins to weep tears down the surface of the painting.

Time bombs. A game of whack-a-mole. I have calculated that there are a finite number of moles to whack. Not all masses of white present this problem, and the number of paintings that exploit white in this manner are a limited number. This is my consolation, an armor of determination and fidelity to my body of work as an artist to make things right for my collectors.

Since I paint in impasto rather thickly, the question of drying is usually the first I have to answer when I present my art work. My answer is well rehearsed: they dry from the exterior to the interior with time, the thicker it is, more time must pass. But time passes and they do indeed dry, usually within a couple of years. And since they first become leather dry and then cookie dry later, and all that we experience is the surface, they are functionally dry rather soon for presentation.

I arrived in NYC looking for a solution to the problem, and found one with a local manufacturer of fine art materials in Brooklyn, Robert Doak. Doak grinds his paint with walnut oil. This guy is super old school, a characteristic East Coast dude -a thick Brooklyn accent, a hard seller, craggy face in your face kind of style, a real hard ass with a smile. He sells his product to many established NY artists, big names. I have made my own tests of alternative titanium white formulations now five years old and counting, and I'm reasonably assured that I have ended this particular problem in my painting practice.

When the time comes to whack the mole, I look for just how extensive the problem is in the painting in question. If it is isolated, such as when the titanium white occurs in highlights of white monads, then the solution is easy. I dry the tears with q-tips soaked in Turpenoid, remove the monad and replace it with better paint. When the use of white is more fundamental, then the solution is more radical: I strip the painting from the support, I re-stretch and repaint the painting. This is an extreme measure that I have performed a handful of times before. The exercise of repainting is interesting, the question of the composition and subject of the painting has already been resolved. The procedure of what was done first, second and third is established history. What is remade is a actually a doppelgänger of what was. And once I have got the feel of the painting in hand, I no longer look to the original and paint only to what is before me. It's like a cloned Einstein, the second Albert is ultimately not the first, but the genes are the same.

The images immediately above illustrate this story. Last month, I flew to Southern California to repaint "The Ragpicker" (#192) from 2003. The problematic white is within the base of the painting, so it had to be remade entirely. The process is involved but ultimately easy. Since I have usually glued the canvas to the wood panel support, the staples are pried out and the old painting is peeled off with determined energy. The result is violent to the original painting, crushing and mauling the dried impasto. I have found that I tended to like the peeled and skinned painting better than ever. This resembles the kind of painting I am making now, much more shredding and acute formal stress. So I usually hang the scalp of canvas from a rod and suspend it from a wire. The resulting painting inspires me to think of ways to produce such a characteristic result in future work... a problem I am still wrapping my head around. There are several issues to resolve along the way, the solution is yet pending.

Now, I am not a young man anymore. With a sixtieth birthday well under my belt, the illusions of youth are long gone. It's natural in this time of my life to entertain thoughts of what is to happen to my oeuvre after I die. What if I have not had the time to whack all the moles from the pre-2012 paintings? What instruction can I offer to a future conservator?

For a collector of fine art, it's natural to expect that the painting that is bought is the painting that remains reasonably so throughout time. Let's forget about the changing colors in Van Gogh's paintings --they were better for it all, in my opinion... but that was pure chance. And when chance strikes as it did with Duchamp's Large Glass, the change is easier to stomach when the artist who certifies it good was the one who was recently dropping meters of string in an act of Dada. Dada aside, change is inevitable in painting after the fact of its making, the ball is still in motion. Paint contracts ever so subtly when it dries. The features of impasto become slightly ever so acute. I have long accepted the changes that happens relatively quickly in the studio, say, when ivory black tends to perspire very small beads of oil on the surface; or when fine wrinkles develop as one strata of color overlays a more temperamental color below it. I have a favorite painting hanging in my home that has baby fists of temperamental alizarin crimson whose fit of wrinkled skin I enjoy as a marvel.

This blogpost is an instruction for the future conservator.

I have in my possession, paintings that weep -not many, maybe three or four- and I rather like them better than before. So for that posthumous moment, I would like to prescribe a solution that I have devised for the lachrymose mole that I have not had the opportunity to whack. In Spain, people hang ham to cure from the ceiling. They attach little cups to catch the fat drippings. Jamón Iberico is so delicious. I have fashioned my own version of the little cups to catch the tears of oil that weep in these particular paintings. Thin gauge wire is twisted into a loop and suspended with a handle that is hot glued to the back of the painting. Palm sized paper cones are fashioned from plastic coated paper palettes material, and fixed into that geometry with PVC adhesive. The cones are tacked behind into the metal hoops with a dab of hot glue and this assembly is positioned in the trajectory of the tears below the painting.

Cry, little paintings. We will catch your tears.

Its ok.

Its ok.

May 5, 2017

Jonathan Meese on Zardoz

In my opinion, the opening decades of the 21st century are gradually revealing the prescience of John Boorman's movie Zardoz. Terrorism, globalism, the haves vs the have-nots, the adored and deplored, the rip tide of science, the prospects of machine intelligence and the internet of things, the crisis of evolution both of our species and our collective cultures, the contradictions and imperatives of freedom, the twinning of immortality and death / oppression and liberation... these are some of the themes that spill out of this movie. In the science fiction that I like, technology in the future will seem like magic to our generation. Was it Arthur Clark who first expressed this idea? Considered a flop as it opened in 1974, ridiculed in a multitude of reviews ever since, Zardoz has achieved a protected status in cult movie followings. It is my wish to enshrine it a little within this blog.

I recently stumbled into a fan video by Jonathan Meese, a Berlin based artist who shares my fascination with Boorman's creation. He was able to interview Boorman in his home in the Wicklow Mountains in Ireland, also famously the set for Zardoz.